Chuck Klosterman on Steely Dan, the Eagles, and his new book, 'Football'

"When you think of the recording of 'Aja' or 'Gaucho,'" the author says, "it’s easy to think of Becker and Fagen as behaving like football coaches."

When I emailed Chuck Klosterman to ask if he would like to have a conversation about two seemingly disparate subjects, Steely Dan and his new book, Football, he responded with a microburst of quintessentially Klostermanian wit.

“I would love to do this,” the cultural critic and longtime Expanding Dan subscriber wrote, “though I realize there are limits to the connection between Steely Dan and football. It’s too bad ‘Glamour Profession’ wasn’t about Vince Ferragamo instead of Spencer Haywood. However, they do obviously mention the Crimson Tide, so that’s something.”

A couple weeks later, Klosterman was on the phone from his home in Portland, Oregon, and he was game to talk about America’s most popular sport as well as our foremost jazz-rock perfectionists.

“I’m in my office right now, and I have a framed black-and-white photograph of Donald Fagen and Walter Becker on my wall,” the 53-year-old said. “I’m not the kind of person who looks for inspirational quotes, but I do sometimes look at that photo, and it reminds me when I’m writing that I should keep trying, that it can get better. Don’t stop. It’s not done yet. Keep working on it. There’s always one more extraneous word that can be removed. It’s something to which I do aspire—to look at writing the way those guys looked at sound.”

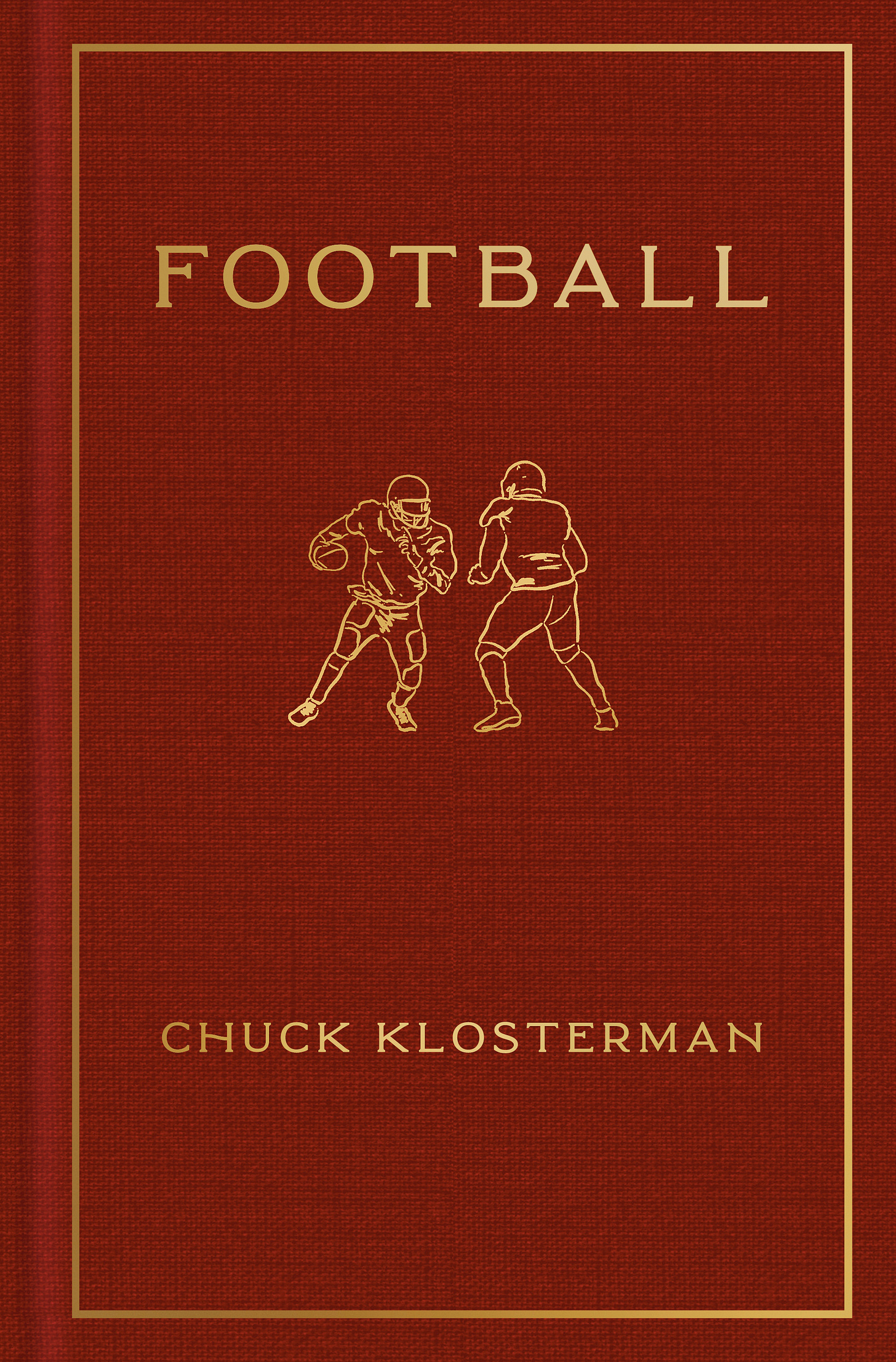

Buy Football by Chuck Klosterman (Penguin Press).

You may also enjoy…

Because this is a newsletter about Steely Dan, I’d like to talk about a comparison you mention in Football that’s made between sports and jazz. Basketball is often thought of as this jazz-like improvisational sport, whereas in football each play is a completely controlled situation within which there are bursts of improvised feats of athleticism. “It’s not that basketball is jazz and football is anti-jazz, or that basketball is jazz and football is prog rock,” you write. “It’s more that basketball aspires to be jazz and football aspires to be petroleum engineering.”

I hadn’t really thought of this until now, but it’s true: When you think of the recording of Aja or Gaucho, it’s easy to think of Becker and Fagen as behaving like football coaches. They are essentially cycling through potential performers, telling them what they want, and also sometimes telling them to do it in exactly the way they want it done. For guys like Becker and Fagen who have such an admiration of jazz, they had a strange unease with improvisation. For a lot of people who love rock, they’re like, “I don’t like jazz. Steely Dan is as close as I get.” But it’s not improvisational, obviously. The idea of Mark Knopfler being brought in and only 19 seconds or whatever of his guitar work ended up on Gaucho? I mean, Mark Knopfler is not some fucking jagoff. That is an incredible thing.

Dean Parks, one of Steely Dan’s frequent session guitarists, once said, “One interesting thing about Donald and Walter is that perfection is not what they’re after. They’re after something that you want to listen to over and over again. So we would work then past the perfection point until it became natural. Until it sounded almost improvised. So it was a two-step process. One was to get to perfection. The other is to get beyond it and to loosen it up a little bit.”

As a writer you have an idea in your mind, and it’s never going to be exactly what ends up on the page. In Becker and Fagen’s case, they knew they were never going to get exactly what they wanted on tape, but they’re like, “How close can we get? Is it possible that by trying to be perfect, we might accidentally do something different that is better?” I feel like that happened on some of their songs where they had a very clear idea of what they wanted the solo to be and maybe the guy played it just slightly off, but they recognized that this is the weird abstraction that makes this profound.

They did perhaps inadvertently foster the perception that they were perfectionists. Just the amount of knowledge about “The Second Arrangement,” in which the song was recorded perfectly, the ultimate manifestation of what they wanted, and then some joker accidentally erased it and they could never recapture that again. Most artists would have been OK with coming close to replicating the song after it was erased, but it was never good enough for those guys. The perpetuation of that story does play into the possibly inaccurate assessment that perfection was all they wanted.

As a Gen X-er who grew up listening to hard rock, you were in your teens and 20s in the late 1980s and early ’90s at a time when Steely Dan’s popularity had severely waned, especially among younger listeners. How did your relationship with the music of Becker and Fagen evolve over the years, and did it involve the Minutemen’s cover of “Doctor Wu”?

Actually, it did not. In fact, I didn’t even know that the Minutemen had done that for years after it happened. But I will say this: In the 1980s, the only music I was interested in was hard rock and metal, so much so that I would not have my clock radio set to music. I set it to the alarm because I was afraid I might accidentally hear pop music. I was dogmatic about this the way you can only be when you’re a high school kid. And because of that, there were certain bands that I hated. Steely Dan was one of them. There was just this collection of artists from the ’70s—Bob Seger, Steve Miller—who didn’t have any relationship to metal and who I perceived as making the music I wanted to hear the least. I would’ve never wanted to hear the Doobie Brothers. There was this whole bunch of music that I wanted no part in.

Then I get to college in 1990. The first thing that drew me to Steely Dan was that the people I met who were really into them seemed extremely interesting. I would meet a guy and be like, It’s really intriguing. He has old ideas in some ways, but he also knows what’s going on, and he makes fun of everything. It was almost like these people had adopted the Becker-Fagen persona. The greatest-hits album Gold was the first Steely Dan album I got. I had heard all those songs while growing up and never cared that much about any of them, but I started to realize how rewarding it was to listen to their music closely. I’m the seventh kid in my family, so I have brothers and sisters who are 18 years older, and I would hear things like the song “FM,” and I would imagine that it was the music they must play in singles bars. There was a show called Three’s Company, and they used to go to a bar called the Regal Beagle. And I could imagine that the music there would be “FM” by Steely Dan.

The more I listened to Steely Dan, the more I realized these guys were funny. But it was funny the way Spinal Tap was funny. It wasn’t funny in a way that made you laugh out loud. It was funny in a way that made you say, “That’s funny.” It wasn’t joking at all, but it was hilarious. Then I got the [Citizen Steely Dan] box set, and I started to appreciate how difficult it is to make something complicated feel simple. That’s one of the things that Becker and Fagen do that’s just so ungodly brilliant—their ability to do things that I know are complicated and yet, at first listen, it just seems completely straightforward like normal radio music. From that period on, when people ask me who my favorite bands are, I say my two favorite bands are Kiss and the Beatles, but level two is Steely Dan and Black Sabbath. Those are the four bands that I care about the most.

My relationship with Steely Dan also became a huge element of my friendship with my coworkers at Spin when I got to the magazine in 2002. I was coming from Akron, Ohio, and I had this fear that I’m going to go to this magazine and every person who works there is going to be so hip and so contrarian and into only the coolest thing happening at that moment. But as it turned out, we all just wanted to talk about Steely Dan, and it was great. We’d go to the bar and then head back to someone’s apartment and there would always be an argument over which Steely Dan record to play. A bunch of us went to see Steely Dan at the Beacon Theatre, when they were playing certain albums live in full, and we had a huge dispute over which record we wanted to see.

Around that same time, the Yacht Rock series debuted.

I would say that was the period when it became too OK to say you like Steely Dan. There’s a Judd Apatow movie [Knocked Up from 2007] where there’s an argument about Steely Dan—Paul Rudd’s character likes Steely Dan and Seth Rogen’s character doesn’t like Steely Dan. That’s when I was like, “I guess this has really moved into a different phase now. Never again will anyone ever be surprised by someone like me liking Steely Dan.” And it had to be satisfying for Becker and Fagen in some sense. They weren’t guys who were easily satisfied, but there had to have been some satisfaction in that period to realize not only was their music being reevaluated, but it was being done by the people who seemingly cared about music the most. It wasn’t like when “Bohemian Rhapsody” got used in Wayne’s World and that song became massive, and now people who had never previously considered Queen their kind of music suddenly like Queen. The people who reassessed Steely Dan seemed like people who’d been thinking about it for 30 years and finally were like, “OK, yes, it’s great.”

I’ve always thought one interesting thing about Steely Dan was that the more isolated and obsessive and indulgent they became, they managed to create work that was increasingly commercially successful.

And we associate Steely Dan with being in the studio forever perfecting things on the most granular level, but they put out a record in ’72, ’73, ’74, ’75, ’76, and ’77. They were in the studio for a long time, but you can’t say they weren’t prolific. When Kevin Shields from My Bloody Valentine disappeared for all those years [after Loveless] and then finally came back, the album he came back with [m b v] wasn’t as good as the thing he’d left off with, but also it felt like he had completely separated himself from the idea of being a commercial musician. I am particularly drawn to geniuses who also want to be conventionally commercial, because I can’t think of something that’s much more difficult, and Steely Dan never stopped being commercial. There’s no album in their catalog where you can say, “Well, this is the record where all they cared about was the art. They didn’t give a shit if it sold at all.” They were never like that. I love Eddie Van Halen, and one of the things I think is amazing about Eddie Van Halen is that his work never starts bleeding over into prog rock. He was never like, “This is not going to be a rock record. I’m going to do all John Fahey acoustic stuff.” He was always like, “I’m making rock music for a four-piece rock band. I’m a genius trapped inside of this paradigm, and that’s what it’s going to be.” That’s how I feel about Steely Dan, too—that Becker and Fagen are masters of doing the most sophisticated version of something that can still be on Top 40 radio.

It’s hard to find other examples of that where it happens so often for so many years. I mean, there are many examples where someone who is not a conventional pop artist, who’s really seen more as an avant-garde individual, makes a song and crosses over with a hit single that is an interesting little footnote to their career. The Butthole Surfers, for example, had a song [“Pepper”] that was on the Billboard charts. But Steely Dan is not like that. Steely Dan is like, “We do this thing where we’re trying to make these records as flawless as possible. We’re thinking about musical ideas that are very complicated. We’re using lyrics that will not make sense. And then if we’re asked to explain them, our explanation will not be helpful. Yet our music is going to be on the radio.”

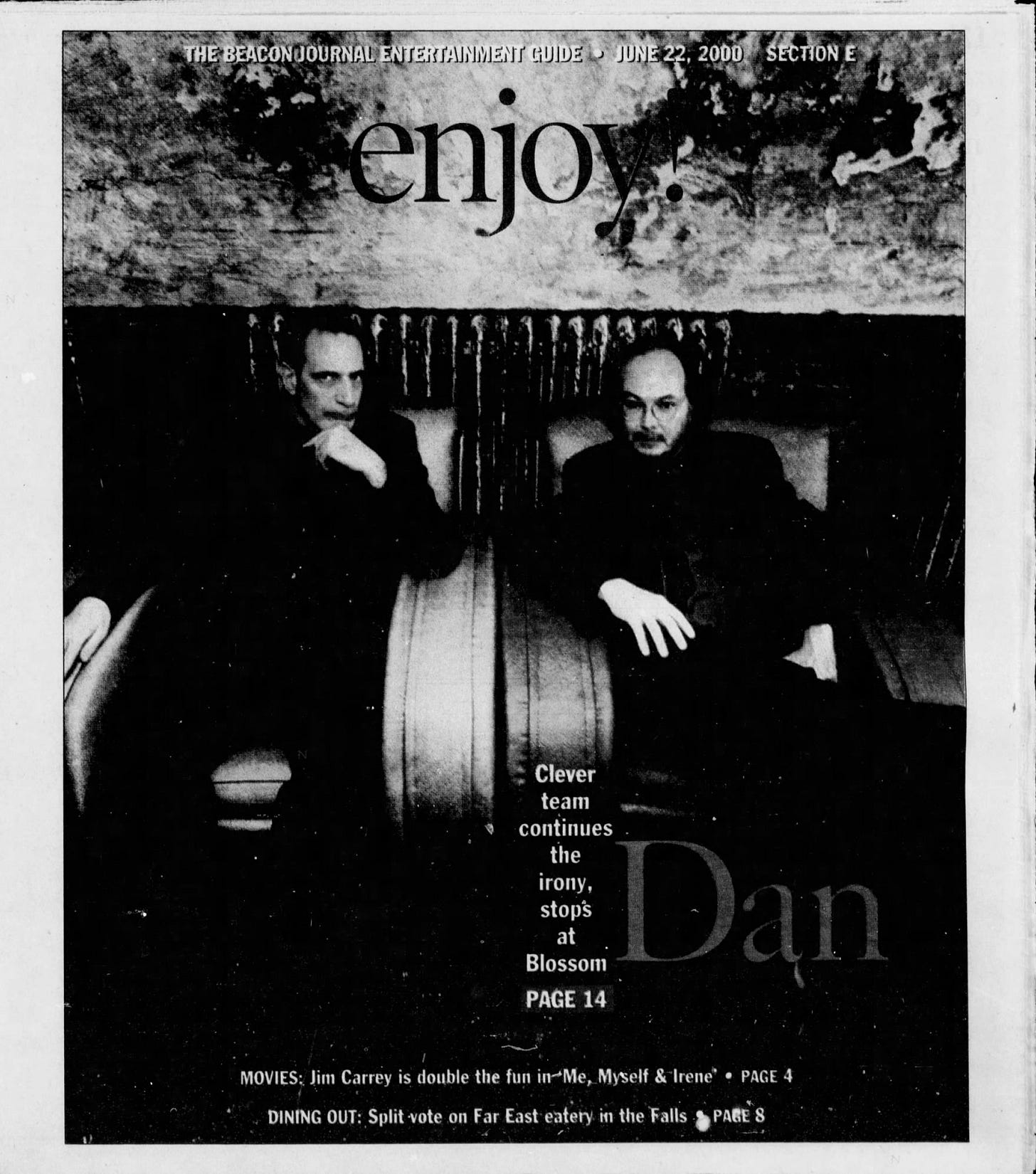

I did an interview with Donald Fagen when I was at the Akron Beacon Journal, and I asked him the meaning of various songs, and it was completely a waste of time. I asked him about “Time Out of Mind,” and he’s like, Oh, we didn’t think anyone would know that the obscure term “chase the dragon” was about heroin.

I actually turned up that piece in a newspaper archive search.

I’m sure you saw the humiliating aspect of that story. I don’t even like admitting this, but there was a copyediting issue, and I spelled Donald Fagen’s name wrong for the whole goddamn piece. But you know how many complaints we got? Not one. I was writing stories every day, so of course I made mistakes. But to this day, I have to believe that Fagen’s name got changed by the copy desk.

Read Klosterman’s interview with Fagen in the Akron Beacon Journal from June 2000.

You wrote an interesting essay for Esquire some years back about the value of having a nemesis. And to Steely Dan, the Eagles served that role in the ’70s, even though they shared a manager in Irving Azoff.

My take has always been that the Eagles want to be Steely Dan’s rivals, and Steely Dan doesn’t care. I’ve always thought that the Eagles were excited Steely Dan mentioned them in “Everything You Did,” that the Eagles saw the fact that Steely Dan cared enough to namecheck them in a song as a compliment, even if it was done pejoratively. And Steely Dan, I would guess, didn’t care that the Eagles mentioned “steely knives” in “Hotel California.”

In your book I Wear the Black Hat, you write about how for many years you despised the Eagles until you woke up one day and realized you were no longer able to hate rock bands. I experienced a similar evolution. I can now enjoy many Eagles songs, but back in the late ’90s and early aughts I think I watched The Big Lebowski one too many times and internalized the Dude’s “I hate the fuckin’ Eagles, man” sentiment.

That actually affected me too. I’m embarrassed to say that now because it’s the most non-musical reason for having an opinion about music. But I was warped by the idea that a person who sees the world in this way sees the Eagles as the single worst thing to listen to. It actually made me a little more interested in the Eagles, and also more performatively against them. And then at some point that eroded too, and I matured out of that phase. We always want to believe that when we’re stating our opinions, we’re talking strictly about the music. But that’s almost never the case. The reason rock music was such a meaningful art form, besides being the only art form specifically for young people, is that it had all of these ancillary meanings. So, of course, there’s also the subjective effect of injecting your feelings into the music.

When we started talking about the Eagles and the importance of a nemesis, I initially thought you were going to talk about the Steely Dan song “My Rival.”

I love that song. The imagery is fantastic, but for some reason it’s often seen as the weakest track on Gaucho.

To me, it feels like the template for what would become a lot of Hold Steady songs. The way Fagen describes the rival seems like how Craig Finn would describe the guy. Gaucho, for a very long time, was my favorite Steely Dan record. Maybe part of the reason I felt that way is because rock critics dismissed it for being too slick. It seemed to be for a lot of people writing about music a bridge too far. Too polished. But I think that the number of good songs on Gaucho might be the most of any of their records.

It’s defensible. Particularly among very online younger people, Gaucho has become the most popular of all the Dan albums.

This is fascinating to me. So Aja is not that record?

There’s something about Gaucho. Maybe it’s the lore around it as the zenith of their maniacal obsession with perfection, or the fact that it was shrouded in Becker’s drug addiction. All the drama behind the scenes might give it some kind of extramusical appeal.

For me these days, if somebody says, “Let’s listen to Steely Dan,” I reach for The Royal Scam. That’s the record I tend to want to hear now. That was not the record I would’ve picked from them even 10 years ago. Like the Beatles and to some extent the Grateful Dead, one of the upsides to Steely Dan is that you can hear a song for 25 years, and then suddenly one day it’s like, “Oh, ‘The Caves of Altamira’ is my favorite song.” A lot of people have this experience with Steely Dan, where you age into your appreciation of the music, and that’s really satisfying.

Turning to Football, you frame the book as intended for a reader in a future society in which football has receded from the culture to help that person understand why the sport was once so dominant in American life. What inspired you to adopt this approach?

The main thing is that my intent was to write about football in a way that discusses its meaning almost as if that meaning has passed. Because I do have this fear—and I have this fear about lots of things about culture—that as the world changes and as these things recede from the collective understanding of what they are, attempts to describe why something was important end up being conducted by people who are distant from the experience itself. So they look back on something and extrapolate meaning, and that meaning is always at least partially inaccurate to those people who actually experienced it. If I try to write about the Bronze Age, for example, I’m not going to really be able to capture the inner lives of the Bronze Age citizen.

So I wanted to do a book for this hypothetical person in the future to get a sense of what the present is really like. My book But What If We’re Wrong created the idea in my mind of doing books that are intended to one day serve as resources about the past. But another thing is that the book-publishing industry—publishing in general—is going through a complicated period, where now the assumption is that anything that’s happening in the present can really only be addressed by things like podcasts or Substack newsletters or social media. The idea of writing about something current in a book that then comes out a year later is really antithetical to the way culture operates. You want the book to be interesting to the person who’s buying it now, but that person may have the expectation that you wrote this a year ago, and it is already old. So as an author, you almost have to correct for that.

It’s so tempting when you’re writing a nonfiction book to make references to Trump, for example, because he seems to infiltrate everything, or to make references to Taylor Swift, because she’s the last extension of the monoculture, or to any of these things that seem to be the last remaining residue of a culture everyone shares. But those things are what date a publication or date a book. In But What If We’re Wrong, I think I only mentioned Trump once, but I regret that I did, because it ties the book to a very specific moment and I’m increasingly trying to get away from doing work that seems essentially interlocked with the world in which I wrote it in.

One of the through lines of the book is your notion that football, however popular it is today, is ultimately doomed. “In the same way imagining the end of the world is easier than imagining the end of capitalism,” you write, “it’s easier to envision a dystopia where football is omnipresent than a utopia where autumn weekends are filled with nothing except sweaters and pumpkins.” So how do you envision football essentially falling off a cliff?

Part of it has to do with the idea that the sheer size of football makes it fragile. Right now football is more popular in the United States than every other sport combined. So it would almost seem as though the likelihood of football swallowing up all the other sports is greater than it disappearing. But the largeness of football demands it never stop increasing in size. You’ll hear something described as “too big to fail.” Well, the NFL is too big to stop growing, and nothing that large can exist in perpetuity, because as the culture changes the big things become more vulnerable than the small things. If you use the analogy of the end of the dinosaurs, the largest dinosaurs were the most at risk after the asteroid hit. The small ones could find ways to survive.

The other thing is that even though football is increasingly popular, the relationship people have to the game itself is constantly decreasing. Fewer and fewer kids play football. For a lot of parents, the idea that they would let their kid play this dangerous sport when there are so many other options—it’s almost like you’d be seen as a bad parent, in some people’s minds, for doing that. So while football is expanding as an entertainment entity, it’s eroding as a social glue of community life. My vision is that when the largeness of football causes this cataclysmic failure, there will not be a superstructure underneath that will say, “We’ve got to save this.” I don’t think that football in the future will have the meaning to people’s lives the way it does now, in particular the way it did in the recent past. Football is important because it really describes American culture in the 20th century, but we’re no longer in the 20th century. So modern football, the modern NFL, is the football of the past on autopilot, and it’s still skyrocketing forward, but the thing that made football important is no longer part of American lives.

You write extensively about the marriage of football to television, and how an eventual decline of advertising on TV may affect football more than our aversion to the CTE-inducing violence of the sport.

The first big essay in the book is about football’s relationship to television, which in many ways is a semiotic argument. It doesn’t really seem to be about football as much as it is about the experience of television and how television works for the consumer. Now, all the details in it are about football games and the way football is filmed and all of these things, but it’s a little strange in that I think somebody who might read that chapter on football and television might say, “Well, this seems more like communication theory. This doesn’t really seem like football.” I was tempted to move that essay deeper into the book because I had the idea that maybe I should really front-load some of whatever hardcore football stuff is in this book, but I ended up believing that would be wrong because the most important thing should be addressed first.

Television, you write, is accidentally the perfect way to consume a football game. It’s such an effective presentation that when someone is attending a live game, you say, they’re subconsciously taking the on-field action they’re seeing and translating it into a televisual experience in their mind. It made me realize I’ve done this myself.

I’m really glad to hear you say that, because I will admit it is a completely impossible thing to prove. I can’t get inside people’s minds and say, “This is how you’re actually viewing football games.” I’ve thought about it a lot and I have what I think is a pretty strong theory explaining it. But again, it’s not exactly research you can do in a lab. This book really is closer to criticism of football the way books about criticism usually involve music or film or art. So there is some subjective projection.

Another idea from the book that I also found intensely relatable is the feeling that any random NFL game, even if it’s a Thursday night contest between two losing teams, is somehow a better television product than, say, the Oscars. I will make plans to watch Monday Night Football without knowing who’s playing. What I do know is I’m going to be consuming an NFL television product, and that’s enough. Is that how it is for you as well?

Oh, absolutely. Of course, you might have a little more psychological investment if the Bills are playing the Patriots for the AFC East title. But in many ways, I have the exact same experience watching the MAC on a Tuesday night where it’s Kent State playing Marshall. Because the thing is, when we talk about TV, if I were writing the New York Times TV column, I would spend a lot of time talking about the content of the program: Who are the characters? What is the theme? But in truth, what I think really gives people satisfaction is the form of television. A lot of times the way TV is formally constructed is a mystery because it becomes invisible when it’s done well. And the thing about football is it is formally brilliant as a television product. This was accidental. When they started playing football in the 19th century, football on television was an impossible thing to imagine. But the way it is created, the way we see it, the way the play stops after every down—all of these things that are even sometimes seen as a negative are actually subconsciously very satisfying.

When people are trying to criticize football, they often mention this Wall Street Journal story from 2010 where a group of researchers proved that in a three-hour NFL football game, there’s really only about 11 minutes of action. And this has been held up as evidence that we’re insane for liking football: How stupid is it to watch a three-hour production and see only 11 minutes of action? But as it turns out, 11 minutes is the perfect amount. We trick ourselves into thinking that what we want is nonstop simulation at the highest possible level, and yet that becomes deadening. There’s a hypnotic effect having these continual breaks that allow you to contextualize what you’re experiencing. And football, just by chance, does that perfectly.

You can watch the game while checking social media, drinking a beer, daydreaming. You once said watching football allows you to slip into an almost meditative state where you can think about your work, think about your writing. Is that part of the pleasure of watching football for you?

Absolutely, particularly in a big-picture way. I don’t really watch soccer, but let’s say, for some reason, I find myself in a situation where I’m going to watch the World Cup final. I’m with friends who are having a party and I haven’t really followed the tournament, but I’m watching this one limited experience. I want it to be as exciting as possible. I don’t want it to be meditative. I want it to be ultra engaging. I want to be on the edge of my seat for the entire match. But if I were to watch soccer several hours every weekend for years, that’s not how I would want it to be. I may think I do. It seems logical to say that. But actually what I want is an experience that’s made for this abstract perpetual relationship, and football has managed to do that. Certainly it wasn’t the intention of the NFL or college football or even the networks. It just happened that way.

Sticking on the television element, do you remember in 2013 there was that Super Bowl where there was a blackout midway through the game?

Yes, it was the Ravens and the Niners.

It threw into relief truly how much those games are a television product. It made me wonder if there were ever a blackout where the lights stayed on so the crowd in the stadium could continue to watch the game and it was safe for the players but the television cameras for whatever reason were unable to power up, would the game continue? It’s one of those “tree falls in the woods” questions. Can a football game go untelevised?

It’s a fascinating question. Let’s say this happens to a normal football game during the early window of games on a Sunday. For whatever reason, the cameras don’t work. Some cyber attack has made it impossible to transmit video. Well, if there were other games happening, they could be like, “We can still play this game without it being televised. We’ll just have to give people feeds from different games.” Or the people in the local area would get NFL RedZone for free that day. But if it were the Super Bowl, they would not play it. There’s no way. They would have to say, “The game won’t start till the cameras work.” And if they couldn’t fix it by that day, the game would be moved a week. I would be interested to see if there’s actually language built into the [broadcast] contract. What would be even more mind blowing would be if the game couldn’t be shown on TV, then you would have all these people in the stadium filming it on their phones, and the entire world would experience the Super Bowl through Twitter and Instagram. That’s a crazy thing to imagine, but at the same time, not so crazy.

There’s a portion of the book about Texas and its obsession with football. It made me think of that scene in Richard Linklater’s film Dazed and Confused, which is, of course, set in Austin, when Randall “Pink” Floyd ends up at a little league game and an old man walks up, grabs his bicep, and says, “Is this arm ready to throw about 2,000 yards this fall?” This guy knows how many upperclassmen are going to be on the team.

My wife actually wrote the oral history of Dazed and Confused.

I loved it. Great book.

And that’s a very good scene in that film because it feels very true to anybody who’s ever been in a small town where football was important. When I was growing up in my small town, if you would’ve gone into the local café during the fall, there would be old guys talking about the high school football team, and it was the same conversation through multiple generations where it was as if the parts were just being replaced, which they were—kids graduate and new kids replace them. And that is really the thing that I would argue is socially disappearing, and why when I say in some distant future, if football were to find itself in some catastrophic economic situation, there would not be this sense from the populace that this thing must be saved. That old guy from 1976 depicted in Dazed and Confused—there might be an old guy like that who still exists today, but will such an old guy exist in 50 years? I don’t think so.

I’ve gotten a lot out of this newsletter over the years but this installment has me seriously considering canceling my subscription. Why you would ask a guy who’s favorably compared KISS to the Stooges about anything related to music is beyond me.

I'm curious if Klosterman is a musician, or has a musical background. I say that because-and I may be the only one who feels this way-I think far too many people misunderstand this idea of perfection when it comes to Steely Dan. Becker and Fagen wanted to make records that would 1) best represent their musical ideas (and influences), and 2) stand the test of time, meaning you could listen to them over and over and both appreciate the musicianship and find the many nuances within. As a musician/songwriter/recording artist (I don't care how pretentious that might sound), there are 3 things that matter most: Groove, feel, and sound. And I believe that's what Becker and Fagen strove for in their records. You can have great songs, great arrangements, great players hitting the notes and being in time, and still say it ain't quite there. And like all things artistic-and they were creating works of sonic art-the results are subjective to what they heard in their heads.

Asides: My Rival is a serious groove tune and the slyest song on Gaucho.

On football on TV and as a reference to the Dan; football on TV is predicated on the movement on the ball (think melody). It's does not stay in the wide field format that the coaches use to call in plays and evaluate how the game went. But it is the most informative way to watch the game if you know what you're looking for. The casual viewer does not care about who lines up where, what defense their in, or what the shifts just prior to the ball being hiked infer; they just watch where the camera-at that time-takes them. Similarly, you can approach a Dan record as just something to listen to, or you can pull back and listen carefully to all the moving parts and how they integrate the groove, the feel, and the sound.