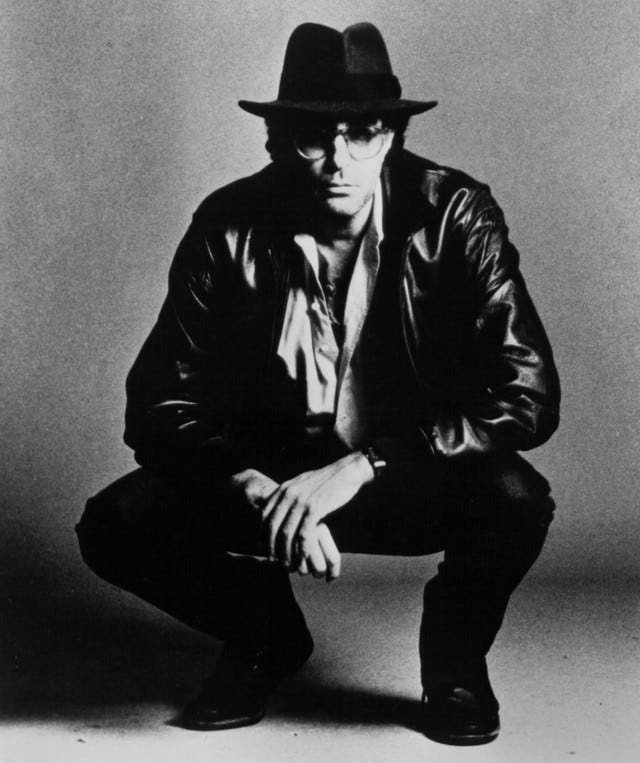

'Librarians on acid': a conversation with Kenny Vance

No one would listen to Walter Becker and Donald Fagen's songs. Then they found their first champion in a member of Jay and the Americans.

In the new series “From the Archives of Brian Sweet,” Expanding Dan joins forces with the author of the definitive Steely Dan biography, Reelin' in the Years, to explore his extensive trove of never-before-published interviews. This edition features Sweet’s lengthy in-person conversation with early Becker-Fagen advocate Kenny Vance, which took place primarily on August 29, 1992. (For additional background on this series, check out my recently published interview with Sweet.)

In late August of 1992, Brian Sweet hailed a taxi in Manhattan and gave the driver an address in Far Rockaway, Queens.

“Why you wanna go there for?” the cabbie asked the slender Englishman. In that part of town, he explained, “They kill you for nothing.”

The warning gave Sweet pause. But the threat of mortal danger could not keep him from his scheduled interview with Kenny Vance. Early chapters of the ambitious Steely Dan biography he had set out to write would rely on the recollections of Vance, a founding member of the hit-making 1960s vocal group Jay and the Americans (JATA) and the first significant music-business mentor of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen.

One day in the late ’60s, the young songwriters, looking typically bedraggled, showed up on the doorstep of JATA’s Mafia-financed music publishing office in New York’s famed Brill Building, trying to peddle their compositions, the lyrics of which they had scribbled in a notebook. “These two guys were like insects, in a certain way. There was no vibe coming from them,” Vance told Sweet. “They were so introverted, I didn’t have a frame of reference. I never met anybody like these guys. They were there, and yet they weren’t there.”

At Vance’s request, Fagen sat at a piano in the office and played embryonic versions of songs such as “Charlie Freak” and “The Caves of Altamira,” while Becker sang the lead vocal. Their offbeat material had put off other publishers, but Vance heard something so different and so new, something that made him believe these two beatniks in trench coats had the potential for greatness.

It wasn’t long before he had arranged for Becker and Fagen to record their first demos. Vance then began shopping the songs to colleagues, including Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. He also invited Becker and Fagen to join the backing band of Jay and the Americans; in addition to gigging with the group, they cut their teeth as arrangers on some of JATA’s final hits. On top of that, Vance hooked up his young charges with a job composing and recording the soundtrack to Peter Locke’s now-vanished 1971 hippie film, You’ve Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You’ll Lose That Beat, and he leaned on his connections to land the Becker-Fagen cut “I Mean to Shine” on Barbra Streisand’s ’71 album, Barbra Joan Streisand.

Just as it seemed they were on the cusp of a breakthrough, Vance and his proteges had a bitter falling-out. In Vance’s telling, Becker and Fagen suddenly grew cold and distant. Without his knowledge, they took the demos he had paid for and slipped them to Gary Katz, a New York pal of all three men, who had recently been hired as a staff producer at ABC/Dunhill Records out in Los Angeles. On the strength of those recordings and Katz’s previous experience working with the duo on an album by an artist named Linda Hoover, Becker and Fagen secured work as staff songwriters at ABC/Dunhill and lighted out for L.A.

When Vance found out they had suddenly quit JATA’s backing band, he called Fagen’s apartment to discuss the decision. A roommate answered and informed Vance that Fagen had, in fact, moved to California that very morning. “So I knew all this was premeditated, and it was all planned,” Vance tells Sweet. “I felt betrayed.”

Now under Katz’s stewardship and backed by a major label, Becker and Fagen soon formed Steely Dan and began recording their 1972 debut album, Can’t Buy a Thrill, which delivered a pair of hit singles, “Do It Again” and “Reelin’ in the Years.” As their careers blossomed, Vance could only watch from afar. “I had spent four years, in my mind, grooming them to [write] songs and maybe to structure them differently because there was a marketplace out there,” he tells Sweet, “and if you didn’t fit into that, there was no way” to succeed.

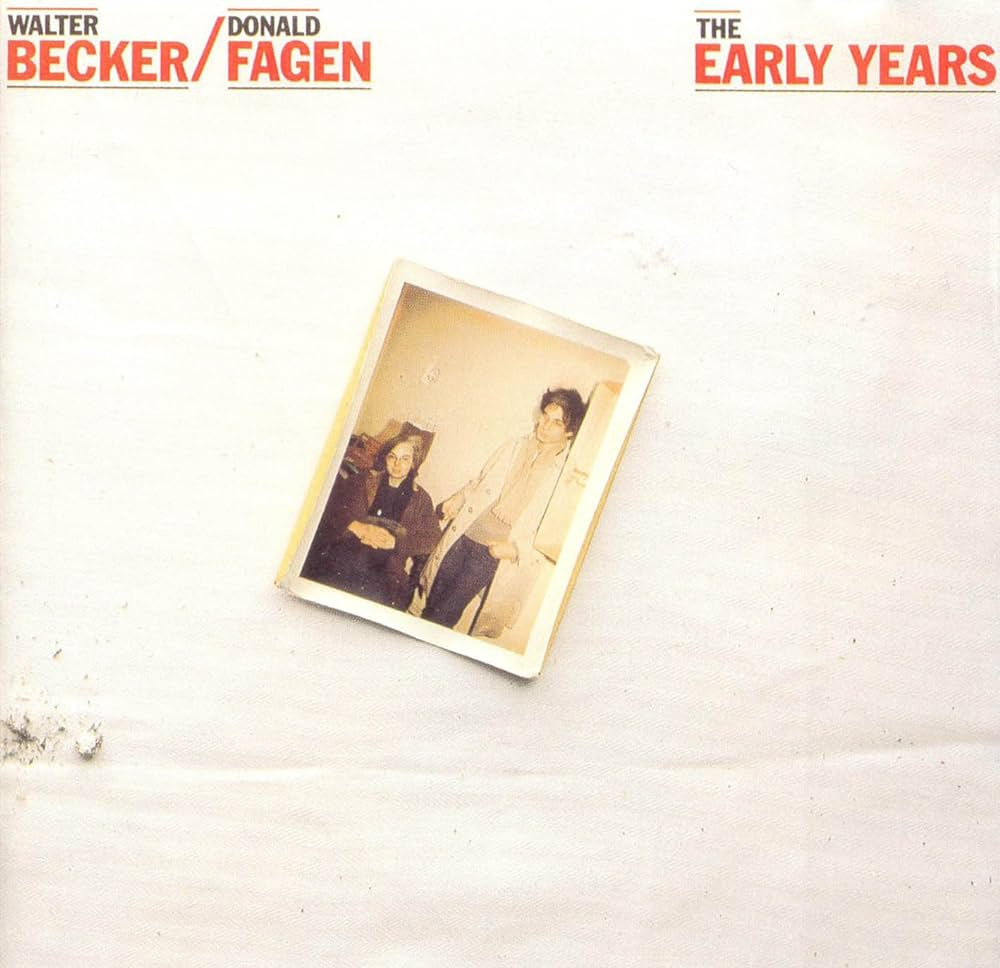

In 1983, Vance would get some modicum of retribution, even if that wasn’t his intention. Piggybacking off the success of Steely Dan, he helped release The Early Years, the first and perhaps only “official” compilation of Becker and Fagen’s pre–Steely Dan demos. In one sense, it was a smart business move; their post-Gaucho hiatus had created pent-up demand for any scrap of new Becker-Fagen material. But he must have known that his unilateral decision to put out those rough-sounding recordings would infuriate his exacting former mentees, and likely eradicate any chance of a future reconciliation.

As Vance and Sweet discussed the dramatic origins of Steely Dan during that summer evening in ’92, the hour grew late. Sweet happily accepted an invitation to stay the night. It turned out that Vance’s home was located well beyond the rough-and-tumble parts of Far Rockaway, in a beach community along the Atlantic coast. In the morning, Vance gave the author a lift back downtown. “Even then,” Sweet fondly recalls today, “we were still discussing all things Becker and Fagen.”

What follows is their full conversation, which has been lightly edited for clarity.