AFTER HOURS takeover edition

Behind-the-scenes anecdotes, never-before-published Polaroids, and other outtakes from my recently published oral history on Martin Scorsese's 1985 black comedy.

During their first tour, Steely Dan played four concerts as the opening act for an unexpected headliner: musical comedy duo Cheech & Chong.

“They were kind of afraid of us, because they were, like, these nerdy musicians,” Tommy Chong told me recently, recalling the March 1973 shows at the Westbury Music Fair in New York and the Shady Grove Music Fair in Maryland. The 85-year-old chuckled at the memory like a stoned surfer. (He later admitted that he had just popped a weed gummy.) “I noticed that they were a bit leery of us,” he said of Walter Becker, Donald Fagen, and company. “But the music—it was incredible, man.”

My interview with Chong was conducted as part of the research I was doing for an oral history of Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, which Graydon Carter’s Air Mail newsletter published on August 12. (Chong and his longtime partner, Cheech Marin, play burglars in the film.) The piece tells the story of how Scorsese, with his career as a major Hollywood filmmaker on the ropes in the mid-1980s, managed to claw his way back to viability with a low-budget surreal black comedy anchored in New York’s gritty downtown scene. Without the redemptive power of After Hours, the ensuing four decades of the director’s career—studded with such gems as Goodfellas, Casino, The Departed, The Wolf of Wall Street, as well as the forthcoming Killers of the Flower Moon—may not have been possible.

For the better part of three months, I interviewed a couple dozen people who lived by night to make the film—among them Scorsese, Griffin Dunne, Rosanna Arquette, and Catherine O’Hara. Scorsese archivist Marianne Bower and After Hours production designer Jeffrey Townsend generously provided reams of invaluable documents: storyboards, memoranda, location-scouting reports, call sheets, script and production notes, and so on.

My initial rough draft was the size of a small book. I machete’d it down to about 14,000 words. Then my editor—the unwaveringly patient and kind George Pendle—chopped it in half out of necessity. As the story got leaner, the narrative gained a more propulsive pace, not unlike what Scorsese said about cutting After Hours with his longtime editor, Thelma Schoonmaker: “We found that the faster we moved, the funnier it got.” Along the way, some illuminating and entertaining anecdotes were excised, and I didn’t want to leave them on the cutting room floor forever.

What follows is my original introduction to the oral history and some choice outtakes, as well as behind-the-scenes Polaroids from the Oscar-winning makeup artist Valli O’Reilly, which are published here for the first time.

For Martin Scorsese, the story of his 1985 yuppie horror-comedy After Hours begins on Thanksgiving Day 1983. That morning he received some news that landed like a Jake LaMotta uppercut to the chin. Over the phone, Paramount Pictures chief Barry Diller informed the director that the studio was essentially dropping out of The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese’s long-gestating passion project.

Scorsese had been consumed with making the film since actress Barbara Hershey introduced him to Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis’s controversial 1955 novel while they were shooting his second feature, 1972’s Boxcar Bertha. Scorsese tapped Paul Schrader, the writer of Taxi Driver and co-writer of Raging Bull, to pare down the complex 500-page doorstop into a filmable 90-page screenplay. Like the book, Scorsese’s film would explore the concept of hypostatic union: the dual nature of Jesus Christ as both fully human and fully divine—a flesh-and-blood person wrestling with fear and doubt and earthly temptations as he’s called upon by God to sacrifice himself for the sins of mankind.

By November ’83, the director and his crew had completed nine months of preproduction work. Scorsese had flown around the Middle East to scout locations, finally settling on Israel. Costumes had been made. Sets were built. Harvey Keitel, cast as Judas, had dyed his hair betrayal-red. Aidan Quinn, in preparation to assume the role of Jesus, had starved himself.

Prior to Paramount’s withdrawal from Last Temptation, Scorsese’s stock had already been falling in Hollywood. His 1980 boxing biopic Raging Bull held its own at the box office as well as the Oscars, but his 1983 follow-up, The King of Comedy, was a commercial and critical flop (though it has since been reappraised). Paramount’s lack of faith in Scorsese was also symptomatic of a studio system that had grown risk averse, wary of investing in director-driven projects in the wake of the debacle surrounding Heaven’s Gate, Michael Cimino’s 1980 epic western, whose infamously troubled production financially crippled United Artists. On top of that, American religious fundamentalists had been waging a months-long holy war against Last Temptation, bombarding Paramount’s parent company, Gulf and Western, with protest letters and calls that made the corporate brass anxious.

In December, Scorsese slashed the proposed budget and shooting schedule in half. But when he brought the more modest plan to Paramount, Diller told him in no uncertain terms that the studio was simply no longer interested. The project was dead.

Scorsese felt utterly demoralized. “It wasn’t just the cancellation of a movie, it felt like the cancellation of my viability in the movie business,” he says today. “In pulling the plug on this project on which they had already spent millions of dollars, they were sending me a very clear message. And the message was: go away.”

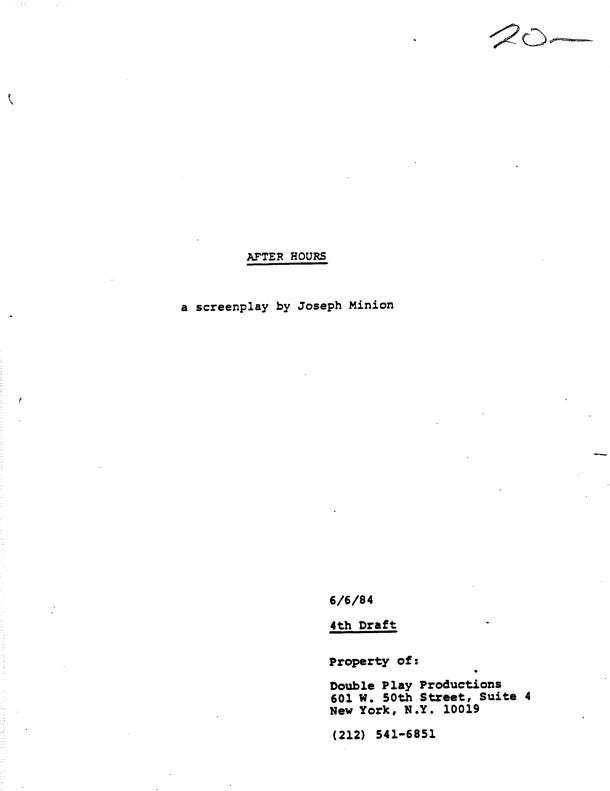

Because he is Martin Scorsese, he decided that the most effective way to exorcize his demons would be to make a film—and quickly. He was offered Beverly Hills Cop (then a Sylvester Stallone vehicle) and other projects he felt weren’t worth his time. Then his lawyer handed him a script called A Night in Soho. The screenwriter, Joseph Minion, was a young unknown. But a familiar name was attached: Amy Robinson, who had a memorable role in Scorsese’s 1973 breakout Mean Streets. She was developing the project with her producing partner, the actor Griffin Dunne. He was riveted by the tale’s many unexpected twists. “It was like a Kafka novel set right around the corner from where I was living,” says Scorsese, who had recently moved into a loft in Tribeca.

He also recognized something of his own predicament in that of the film’s protagonist, Paul Hackett, who seems to slip through a crack in the sidewalk of his life and into an anxiety dream made real. The Manhattan office drone—who would be played by a deliriously slapstick Dunne—leaves behind his blandly comfortable Upper East Side existence late one night to meet up with a mysterious and alluring woman (Rosanna Arquette). On the taxi ride to Soho, his money suddenly flies out the window, leaving him stranded in what’s depicted as a seamy, rain-soaked village sparsely populated by artists, punks, gays, and criminals.

During his increasingly harrowing return journey, Paul encounters an ensemble of colorful characters: a narcoleptic sculptress (Linda Fiorentino) and her leather-daddy lover (Will Patton), a barmaid unfashionably trapped in the go-go 1960s (Teri Garr), a saloon owner given to fits of rage (John Heard), a tetchy Mister Softee truck driver (Catherine O’Hara), and a lady who lives beneath a nightclub (Verna Bloom). Eventually, Paul is pursued by a lynch mob that mistakenly believes he is responsible for a series of burglaries actually being perpetrated by a pair of small-time thieves (Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong).

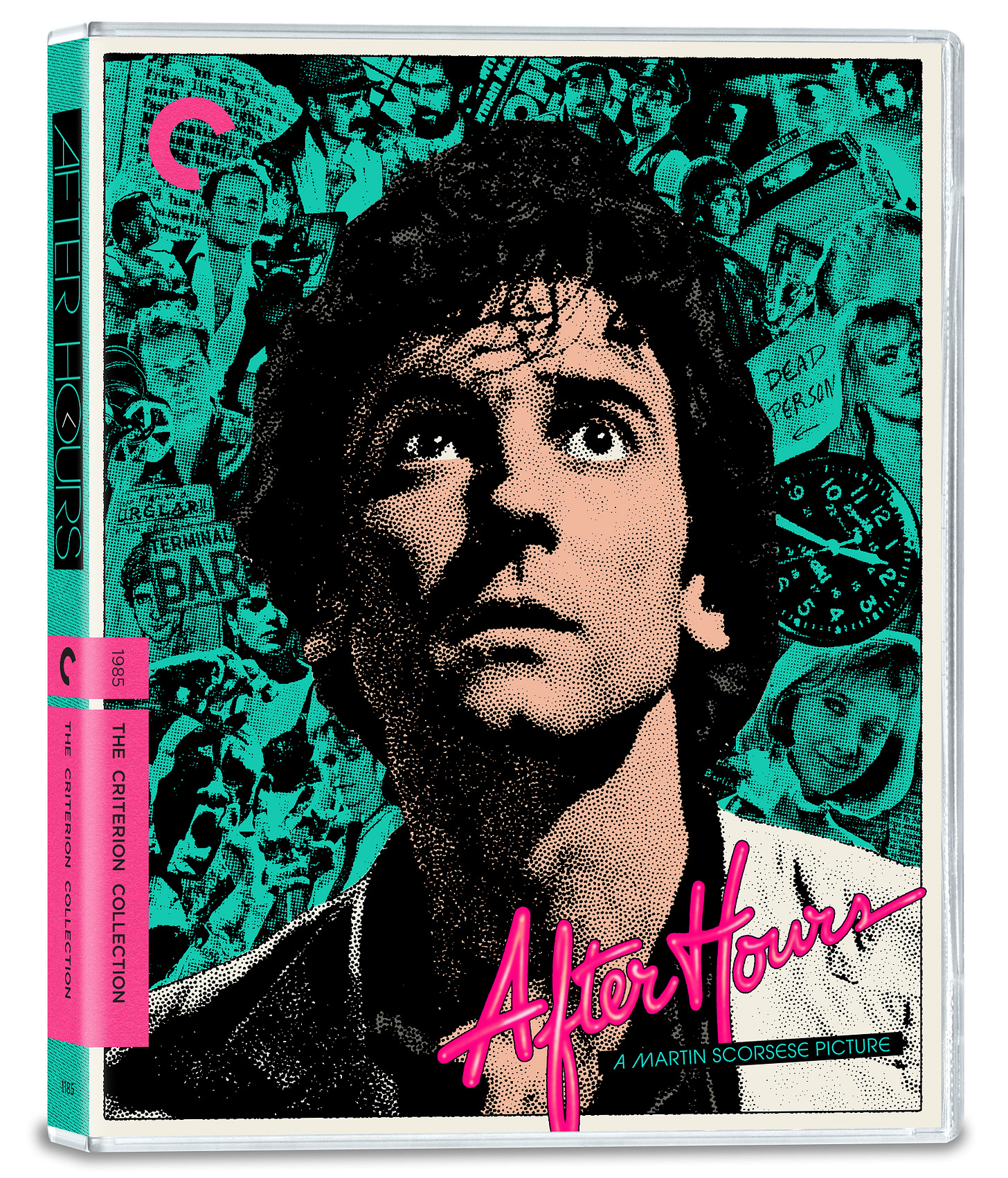

Like Paul, Scorsese felt lost in a kind of pitch-black netherworld. And appropriately it would be this eccentric little film about one man’s survival that would give him a shot to claw his way back to relevance. By the end of shooting, Scorsese would tell his collaborators that the experience had restored his love of filmmaking. After Hours proved a success at the box office and went on to earn Scorsese the Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival. It also gave him the cachet to do The Color of Money, which he then followed with The Last Temptation of Christ (resurrected with Universal Pictures). Last month, the Criterion Collection released a long-awaited Blu-ray edition of After Hours, a lovely 4K digital restoration approved by original editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

“Different rules apply when it gets this late. You know what I mean? It’s like after hours,” a diner waiter says in the film’s titular line, informing Dunne and Arquette that their bill is on the house. Similarly, for Scorsese, different rules applied when it came to After Hours, which saw the director returning to his early days of working quickly and cheaply on the streets of New York. Through eight weeks of all-night shoots during the summer of 1984—fueled by his mother’s Italian cooking and a fierce will to prove himself—Scorsese managed to pull himself out of one of the darkest periods of his career the only way he knew how: by making a movie.

Meeting Marty

Griffin Dunne (producer; “Paul Hackett”): Many years before After Hours, I had a ridiculously funny first encounter with Marty. This agent, Kitty Hawks, who was brand new on the job, sent me in for a meeting with him. Kitty was the daughter of Slim Keith and Howard Hawks. She knew everyone in Hollywood, including Marty, who was then making Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore. Kitty had clearly never read the script. I went to the Warners lot where Marty had a little trailer, and I knocked on his door. I was maybe 17. He opened the door and said, “Yes?” I said, “I’m Griffin Dunne. I have an appointment with you.” He goes, “For what? The kid in the picture is 11 years old!” I turned to walk away and he said, “Come in, come in. Let’s talk anyway.” We talked for, like, 45 minutes, and I was in love with the guy. I never dreamed that years later I would actually end up working with him.

Amy Robinson (producer): I met Marty when I was a young actress. Brian De Palma was a friend, and he was living at a little beach house in Trancas out in Malibu with his then significant other, Margot Kidder, and his best friend, Jennifer Salt, who are the stars of his film Sisters. They said to me, “Why don’t you come out and stay for a while?” It turned out to be the epicenter of these filmmakers and actors who were then getting their foothold in Hollywood. That’s where I met Marty. Later I got to audition for Mean Streets and was cast as Teresa [the girlfriend of Harvey Keitel’s character and the cousin of Robert De Niro’s character].

Origins

Amy Robinson: Griffin and I finally met at a party in New York in the late ’70s through a mutual friend, the writer Jesse Kornbluth. Griffin was very charming, and we hit it off. I knew his aunt and uncle, Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, who were also part of the crowd at De Palma’s beach house. He introduced me to another friend of his named Mark Metcalf. The three of us were at loose ends as actors. None of us were getting work.

Griffin Dunne: Amy, Mark, and I formed Triple Play Productions. With our unemployment as actors, we had all this creative energy. We workshopped Sam Shepard’s Cowboy Mouth just to keep busy. Amy and I were voracious readers, and she was a great fan of Ann Beattie’s short stories from The New Yorker. When Ann’s debut novel, Chilly Scenes of Winter, came out, we were in that wonderful place where we didn’t know what to be afraid of, so we decided to make it into a movie. Mark used his money from playing Neidermeyer in Animal House to option the book, and we just went headlong into it, with Joan Micklin Silver, who was actually a bankable director. Mark eventually broke off to pursue acting, and Amy and I continued on as Double Play Productions. We next worked on Baby It’s You, based on a period in Amy’s life. We got John Sayles to direct.

Amy Robinson: In 1981, I went to the first Sundance Lab. I was one of the fellows. The first years of the Lab were really wild and woolly. It was this great idea that Robert Redford had, which was to bring a lot of creative people together in the mountains, some young and some established. One of the people I met there was this Serbian director named Dušan Makavejev. He’s best known for a film called W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism, which he wrote and directed. He was a great character, and he brought along one of his students as a kind of a production assistant. Dušan came up to me and said, “I have a script. It’s about New York, and you’re from New York. You should read it.”

So I took the script back to my cabin up in the mountains that night. It was then titled Lies. It was crazy and dark—even darker than the movie ended up. And I just loved it. It appealed to my dark sensibilities and my New Yorkness and what I loved about New York and the kind of adventure that can happen to you without your even knowing what is gonna happen next. The protagonist, Paul Hackett, has this humdrum existence. He doesn’t know what to do with himself. And he meets this very pretty girl in a coffee shop and figures connecting with her is gonna be a great adventure. And it was—but not exactly what he expected. I called Griffin and said, “I found this script, and it would be a great part for you.” After the Lab, I went out to L.A., where Griffin was, and brought the script with me in a box.

Griffin Dunne: It took me a long time to get through the script. It gave me such terrible anxiety that I had to read it standing up, turning the pages with my big toe, walking away after something awful happened, and coming back to it.

Joseph Minion (writer): I had seen Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out as well as David Mamet’s play Edmond, both of which took place in a single night, and the all-in-one-night structure appealed to me. I was reading Henry Miller but more significantly Norman Mailer’s An American Dream, and though I cannot say exactly how, I know this novel had a profound effect on me and influenced the script. More generally, I was frantically moving from New York apartment to New York apartment then, always moving for a different reason, and it felt like I couldn’t find a home. I’m certain this fueled the frenetic nature of the script.

During rewriting we had tried on some very short calm-before-the-storm foreshadow-y type openings: Paul coldly breaking up with his girlfriend; an acting class with Paul during which the entire set around everyone cracks and collapses like that scene in The Day of the Locust. Many bits were cut, my favorite being an absurd, circular, almost Beckett-like conversation between Julie—the Teri Garr character—and Paul. One thing in the script that was never filmed, to my knowledge, was a moment when Paul climbs one staircase too far in [bartender] Tom’s apartment building and winds up on the roof of the building and there’s a slight fog out there, with Paul just standing on the roof, in a fog figuratively and literally. To me that moment perfectly illustrated how I felt in life at the time, so I was sorry to see that it never made it in, but I understand why: gotta keep these movies moving; I observed that pretty early.

Romance in Soviet Poland

Griffin Dunne: I had met Rosanna years before, while doing a TV movie in Poland called The Wall. Making The Wall was a movie in itself. Poland was part of the Soviet Bloc then. We were supposed to be there for three weeks. We were there for three months because the country went into martial law. Our translators and some of the film crew were rounded up, jailed, and replaced by members of the military. The Summer Olympics in Moscow was going on, and the Americans were boycotting over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. All the food in Poland was being sent to Moscow for the Olympics, so there was almost nothing to eat. On our days off, Dianne Wiest and Tom Conti and Rosanna and I would stand in these long black-market lines to get food. The bright spot was that Rosanna and I had a lovely on-set romance in Poland. You know, I would take off her babushka . . . [Laughs.] Rosanna and I were not together by After Hours. But we had a real familiarity that was very easy to play with.

Casting the supporting players

Will Patton (“Horst”): A lot of people came to theater in those days to cast film, and I was doing a lot of theater back then. Scorsese had seen me in Sam Shepard’s play Fool for Love. It was the original production, and I’d been on the nine-month run, doing eight shows a week. So I went in and met Scorsese, and he was really open and warm, and he laughed a lot. I didn’t audition, we just talked. Not too long before I’d actually lived in an abandoned building in the very area where he had shot Taxi Driver; I knew that neighborhood really well, so Taxi Driver kind of blew my mind. And I knew the world he was trying to capture in After Hours. Maybe a little too well.

Amy Robinson: My oldest friend Robert Plunket, who is a novelist, played the young gay man at the end who picks up Griffin and brings him back to his apartment. He’s the one-man audience for Griffin’s long rant about his horrible night. Bob and I had been acting together back when we were at Sarah Lawrence and at La Mama.

Robert Plunket (“Street Pickup”): I knew Amy and Griffin when we were all starving artists together in the late ’70s and early ’80s. They mentioned that there was a small part they thought I would be good for—as a closeted gay man who goes out wandering the streets at night hoping to connect with someone. They said I should come down and meet Mr. Scorsese. I was very reluctant to play a homosexual on screen. This was a long time ago, and I didn’t want that kind of attention, so I was hoping I did not get the part. He already had somebody else in mind, but suddenly he thought I would be more effective, and the other guy got the boot. The other guy was a very cool, hot, young gay guy, and Mr. Scorsese realized the part would work better with somebody who comes across more like me: shy, insecure, almost catatonic. Scorsese is the straightest man in the world. He’d never had to deal with any of the nuances of homosexuality, but suddenly he had to bring these gay characters to life in After Hours. And I think that he didn’t know how to do it. And then all of a sudden I show up, and he said, “Oh, that’s what it’s all about.” He really trusted me. At first, he felt I should have an earring because he thought all gay men wear earrings, and I had to explain, “No, only out gay men wear earrings.” Little nuances like that I helped with, because he was not of that world at all.

Victor Bumbalo (“Neighbor #2”): My play was running Off Broadway at the time, and someone who was at one of the performances came up to me and said, “I’m working for Mr. Scorsese. Would you like to meet him?” And with my writer’s ego, I thought he wanted to talk about my play! He clarified, “Would you like to audition?” I was worried because I had stopped acting due to offensive material around gay characters. But I think After Hours turned out to be trailblazing for its accepting portrayal.

Location scouting the Scorsese way

Jeffrey Townsend (production designer): Marty was so much more of a stand-up comedian than I ever expected. He’s a hysterical human being. I remember we were driving somewhere to look at a location and Marty’s in the front seat, and a woman rushed out into the street between parked cars into traffic, baby carriage first. There was just something about her using her baby as a traffic tester to see if there were any cars coming that got him started. It was a hysterical ride from there on out. It was delightful to hear him react to the inanity—and insanity—of New York life.

I remember, during location scouting, showing him little apartments that would be Teri Garr’s apartment, Catherine O’Hara’s apartment, John Heard’s apartment, and he rejected them all. And it finally dawned on me that he was rejecting them not because they weren’t the right size for the story and in terms of New York real estate, but because he was getting claustrophobic just scouting them. What I did was found a loft that had street windows and some air-shaft windows in the back. We built some set walls and kept rearranging them up against different windows and repainting them to create three different apartments within that single loft. Most New York apartments have, like, 15 coats of paint anyway. It was inexpensive, and it allowed Marty to step out of the apartment and have a little breathing room.

Budget thugs

Amy Robinson: The film had a very modest budget—about $4.5 million, in the end. The movie was financed by the Geffen Company. As is typical, they hired a bond company to make sure we stayed within the budget. The bond company representatives, who were a little bit like some guys from Mean Streets, came into our office at one point and were acting very tough, and they said, “If you start going over budget, we’re just gonna come in and rip the pages out of the script.”

In praise of D.P. Michael Ballhaus

Michael Nozik (production manager): On the schedule and budget we had on After Hours, we had to get so many shots per day. But Michael was used to working that fast.

Jan Sebastian Ballhaus (second assistant camera; son of Michael Ballhaus): Scorsese had a very detailed shot list for After Hours. My dad was used to shooting 15, 16, even 20 setups a day, so that wasn’t really scary for him. He came from European filmmaking, where there were much smaller budgets and they had sometimes 15 or 16 days to shoot a movie. So he was trained to work very efficiently and fast and make things work—make a plan to somehow get it done.

Griffin Dunne: This was a guy who was used to working quickly and efficiently, and with a very demanding, visionary director.

Amy Robinson: Griffin and I had just worked with Michael Ballhaus on Baby It’s You. We showed Baby It’s You to Marty, and he loved the fluidity of Ballhaus’s camera work. It was the beginning of what would become a longtime partnership.

Michael Nozik: The D.P. always drives the speed of filming. Michael’s speed gave Marty more time on set to work with the actors.

Jeffrey Townsend: The dynamic on a movie set is usually the actors are done in hair, makeup, and wardrobe, and waiting for camera and lighting—waiting for the set to be ready. On a Michael Ballhaus film, it was the opposite dynamic. The actors were getting hassled to get out of makeup and hair and wardrobe. It was such a nice inversion. And directors, of course, love that they’re able to get more done. Michael made setting up the camera moves look easy. He also had a way of thinking about lighting that was brilliantly economical. A lot of cinematographers take pride in their lighting, and so if there is lighting already happening in a space, their attitude is, “Let’s shut all that off and let me start from scratch to demonstrate my brilliance!” Michael was much more like, “OK, the lighting that’s already here is about 80% of what it should be,” and then he would simply augment. It’s brilliant—and it’s faster. One of the secrets is that Michael worked with a gaffer named Stefan Czapsky, who is now a director of photography of renown. Michael trusted Stefan and me so much that we would go pre-light all the sets one or two days before we were to shoot. Michael would then show up on the day of the shoot, turn on the lights, and he’d say, “OK, move this light a foot, and we’re done—we’re lit.”

Jan Sebastian Ballhaus: On his other films, Scorsese spent hours in the trailer waiting for the lighting setup to be done. On After Hours he realized there was really not enough time to walk back to his trailer. So he was able to spend much more time on set working with his actors.

Griffin Dunne: On After Hours, the restrictions on time and budget upped the ante, upped the energy, upped the urgency of making the movie. And it shows in the performances.

Working at night

Jan Sebastian Ballhaus: All the shoots were nights, so lighting could be a bit more challenging. My dad always liked to use available light. He came from a school of using available light as much as possible to give his shots a natural look. We were working with high-speed film stock, pushing that to its limits to be able to shoot at the low light level that we had to deal with. But because of the low light level, contrast sometimes became a problem. There were times we had to take down street lights because there was almost too much light, or put foils on them to dim them down a bit and cut down on the contrast.

Rosanna Arquette (“Marcy”): I wish I would’ve had the blacked-out windows like Griffin had. I could never sleep much during the day. At the time I was living in an apartment at the Mayflower Hotel. It was on Central Park West, between 61st and 62nd Streets, overlooking the park. After a night of shooting, I would just walk around with all this adrenaline. I spent a lot of years as a walking insomniac when I was working. It was terrible.

Jan Sebastian Ballhaus: My dad, my brother Florian, and I were living together in a rented house in New York. We all felt like moles living underground. Everybody else in New York was sun-tanned. We left work at sunrise, tripping over rats on the way home, then spent the day in the apartment with the air conditioning running loudly, trying to sleep.

Cheech Marin (“Neil”): When we started shooting After Hours, I was like, “Oh, man, I’ve been here before!” I had previously lived at 211 West Broadway, so I knew the area well. The thing that the film got spot on is that even in New York, each neighborhood is a small community, and you sort of know everybody from around the way. Everybody in the movie kind of knows each other, and they keep criss-crossing in the neighborhood throughout this crazy night, reporting on each other.

Jeffrey Townsend: It was summer in New York, so it was stiflingly hot in these downtown locations that didn’t have air conditioning. We brought in this air-conditioning truck that had a hose three or four feet in diameter that blew cold air. We would drag that up the stairs of these nasty loft apartments. It had to be shut down when we were filming, but it actually worked.

Cheech Marin: I started to feel like a bit of a vampire. Sleeping all day and living at night totally turned everything upside down, which gave a real sense of urgency and authenticity to the movie.

Jan Sebastian Ballhaus: We were used to eating lunch at 1 a.m. So on weekends, when we were off, we would try to maintain that schedule so we wouldn’t get jet-lagged.

Catherine O’Hara (“Gail”): I was a night hawk anyway. I would do all my writing for SCTV in the middle of the night. I loved staying up late. I felt like everyone else was asleep and all the ideas were mine. It was thrilling to be in downtown New York at night. Something about being on location, especially in a city like New York, where you just feel like I’m in a movie.

Will Patton: I shot something in the early part of the production, and then I came back to do something else in the last week of shooting, and the cast and crew were like different creatures after having done those consecutive night shoots for several weeks. Especially Griffin. He lived it all. The set still felt electric and dangerous, but nighttime shooting in New York for that long was pretty intense. I don’t know what everybody was doing to get through it at that time, if you know what I mean.

Valli O’Reilly (makeup artist): Because the whole story takes place in one night, I had to slowly stress Griffin using makeup. I had to show whiskers developing. Because the film wasn’t shot chronologically, I had to devise a continuity chart for myself. The whiskers were going on and coming off Griffin.

Medusah (hair stylist): Griffin is running through the streets all night and getting rained on. I had to keep his hair wet and wild.

Griffin Dunne: The rain they created on the set was torrential. They were on the roof with hoses just spraying me down.

Robert Plunket: In the scene I’m in with Griffin, he launches into a monologue about the terrible night he’s had, and all the while I’m thinking, Uh-oh, Griffin is losing his mind. He was under a tremendous amount of pressure during the making of After Hours, because he was the star and also a co-producer. There was so much that he had to keep track of, and he was so harried in that scene, that I interpreted a lot of what he was doing as Griffin going nuts from the experience of making the film. It wasn't all acting. He was going a little nuts. You didn’t know where Griffin ended and the character he was playing started. It was all merging into one frantic person. But that only added to the incredible manic brilliance of his performance.

Valli O’Reilly: Marty had so much energy. We would all say, “Thank God the sun is gonna eventually come up,” because he would have just kept going and going until the film was finished. That’s how much he loved his job.

By the time we had to walk home, the sun was coming up, so all the midnight monsters that you had conjured in your brain would sort of disappear.

Renting David Byrne’s loft

Valli O’Reilly: David Byrne from Talking Heads rented me and the hair stylist, Medusah, his loft in Soho, which was walkable to the set. We had both worked with him in the past. He was going on tour, and he let us stay there for almost nothing. It was tough to sleep in New York during the day because it was so noisy. I would put earplugs in. And also David’s loft didn’t have any blinds. So as soon as the sun was up, the whole loft was bright.

Medusah: David’s loft was at Greene and Houston, and it was not unlike Kiki’s loft in After Hours. It was really minimalist, designed in a kind of Japanese aesthetic.

Valli O’Reilly: We’d hear a knock on the door, go downstairs to answer it, and it would be, like, Brian Eno. A call would come through, and it would be one of the Beatles leaving a message on David’s answering machine. One time I picked up the phone, and it was David Bowie. I couldn’t speak, I was so shocked. He was like, “Uh, are you there?”

Medusah: While we were there, Architectural Digest came in to shoot the place. David told us not to let them use the air conditioning. Well, we came back from a night of shooting, and they had opened every window, and left them open, and the place was filled with flies. We had to rush out to find a store that sold fly strips.

Griffin Dunne, raconteur

Catherine O’Hara: Griffin Dunne was full of stories. I dunno if he was making up crap or if it was all true, but every night he had a different story of some insane thing that had happened to him.

Griffin Dunne: The year before After Hours came about, I went to Sri Lanka by myself and motorcycled around. During that trip, I met a German girl named Greta, and we traveled around a bit. Before shooting began on After Hours, she wrote to tell me that she was going to the Midwest to be an au pair but would have a stopover in New York. Greta asked if she could stay with me. And I said yes. So she stayed with me and then left, and I started shooting After Hours. About a week or so later, she called and said, “This has been a disaster. They hate me. I hate them. Can I come to New York and stay with you?” I said, “No, I’m shooting.” She was very upset, and I felt really bad. Toward the end of shooting, I spotted someone sitting against a lamppost in filthy, tattered clothes. I went, “Oh my god—Greta?” I’m thinking she came to New York and now she’s homeless. I was horrified. I walk over to her, lean down and go, “Greta, it’s Griffin. I’m so sorry.” She looks up at me with hatred, screams, lunges at me, and scratches my face. I look a little closer, and it’s not Greta at all. It’s some completely different woman. The crew pulls her off me, and she’s still screaming. The crewmembers are going, “What is wrong with you, Griffin? What did you do to her?” “I thought I knew her!” It was a very Paul Hackett moment.

The key-drop shot

Amy Robinson: The shot of Kiki dropping the keys to her loft down to Paul was a very important shot to Marty. Our crew was very intrepid and felt that they could rig up a camera platform that was falling down from a building with bungee cords.

Griffin Dunne: My cousin Tony Dunne, who had been a carpenter on Baby It’s You, was a set builder on After Hours. For the shot when Kiki throws her keys down to me, Tony designed this contraption with bungees tied to this 45-pound camera that was just simply dropped out a window following the falling keys, with me standing underneath it.

Amy Robinson: I was sitting next to Marty, and both of us were watching these ropes smoking as that platform came down right above Griffin’s head.

Griffin Dunne: It was terrifying. If it hit me, it would certainly have killed me. We did one take, and Amy goes to Marty, “This is a bad idea. I’m not feeling good about this.” And then we did a second take, and one of the bungees came loose and the camera flopped out and nearly landed on me.

Amy Robinson: I was like, “Uh, maybe we shouldn’t do that again. Hopefully we got the shot.” When we went to the dailies, Marty was not happy with the shot. It was shaky. I said, “We don't have the money to do that again.” We had a bit of an argument about it. But [producer] Bob Colesberry went back to the budget and found some extra money.

Griffin Dunne: Eventually, on the last day of principal photography, we did the sensible thing to shoot the key drop and simply put the camera on a crane and dropped the crane down toward me in a nice, controlled way. It took, you know, 10 minutes, and we got the shot that’s in the movie.

The Scorsese method

Griffin Dunne: We shot a lot of tape. There was never any “OK, we got it on the third take.” Marty always wanted to see what would happen on the 12th take. The only place we started going over budget was on the amount of film stock. I was Amy’s co-producer, and at one point she came to me and said, “Listen, we’re way over on film stock. I wonder if you could talk to Marty about that.” And I said, “Let me get this straight. You want me to ask Marty to shoot less of me?”

Will Patton: Scorsese created an atmosphere on the set that was completely dangerous and electric, and yet at the same time really open and welcoming. He made the actors feel free enough to say, “Let me just try this the wrong way.” He had trust and left it open to a lot of possibilities. Because he spends so much time editing, you knew he was gonna find the right moment even if you fuck up.

Medusah: Teri Garr was fantastic as “Miss Beehive, 1965,” and so was her beehive hairdo. There was a shot we did where a bee actually flies out of her hair. A trainer put the bee in a little glass tube, inserted it into her hair, and opened the tube and the bee actually flew out. For some reason that shot never made it into the film, but it was hilarious.

Victor Bumbalo: The first thing Scorsese said to me was, “Victor, don’t act.” He didn’t want you to going over your line readings in your head. He wanted you to be natural, in the moment. He was aware of everything that was going on, every gesture. And you honestly felt like you wanted to do well for him.

Robert Plunket: I was hanging around the set before the scene I was in and noticed that Mr. Scorsese, whenever one of the actors forgot his or her lines, would say, “No, no, no, keep going! Say it in your own words.” The lesson I took away was, “I’m gonna write a monologue for myself!” That’s how stupid I was. When we shot the scene, I went into this long monologue about my dead lover I had lost in Puerto Vallarta during a hang gliding accident. Griffin was staring at me in disbelief, but Mr. Scorsese didn’t mind it in the slightest. Of course, it had to be cut.

Medusah: Once we got into the swing of things, Marty would ask me for a hair trim or a beard trim every week. But what he wanted was to get me in the trailer and find out what was happening with the crew. He loved the gossip. I always know what’s going on. People tell hair people everything. I gave him information that he found funny. He would send somebody over to me to say, “Marty wants to see you in his trailer. Bring your scissors.” He just wanted to key in on whether anybody was unhappy.

The Mister Softee truck

Michael Nozik: It took a bit of convincing for the Mister Softee company to let us have a truck. They wanted to know if we would be tarnishing the esteemed name of Mister Softee. They were worried we were gonna do something with children or make their ice cream seem like poison or something. I had to go out to Jersey to speak with the company guy and try to convince them to give it to us.

Scorsese’s parents

Jan Sebastian Ballhaus: In one of the first scenes in After Hours, you can see Scorsese’s parents, Charles and Catherine, sitting behind Griffin in the diner.

Valli O’Reilly: Charles was immaculately put together. Old-school Italian. You could see your face in the reflection of his shoes.

Medusah: Makeup, hair, and wardrobe were working out of a small Winnebago. It was me, Valli O’Reilly, costumer Deirdre Williams, as well as Marty’s parents crammed into one of the smallest Winnebagos you could get. Charlie Scorsese was the ironer—he would iron all the costumes. And Cathy would bring us homemade eggplant-parmesan sandwiches for lunch. Lunch was at 1 a.m.

Rosanna Arquette: I loved Scorsese’s parents so much. Catherine would sometimes make a big lasagna. It was always delicious. And I loved to sit and hear her stories. Marty would just laugh and laugh.

Valli O’Reilly: His mother would make Marty lunch in a bag every day. He would be too wound up and focused to eat, and she would be so disappointed. So I’d often be like, “I’ll eat it!”

Griffin Dunne: Marty’s parents adopted me. They called me “the boy” and would invite me to dinner at their house because they knew I loved his mother’s food. They started to bring to the set not just a Tupperware container for Marty, but for me as well—meatballs and pasta and just incredible Italian food. We became quite close. I loved both of them. They thought of Marty and me as brothers.

Marty’s friend, the great director Michael Powell, was also on the set quite a bit. He’d show up in a snappy bright orange suit just to see the work being done. He was very paternal to me. I didn’t mention to him that one of the VHS tapes that Marty gave me was A Matter of Life and Death among other Powell and [Emeric] Pressburger movies. I don't know that he knew my name, but he just kept saying, “You’re a fine boy. You’re such a wonderful boy, and I love what you're doing.”

Kiki’s loft

Michael Nozik: Finding Kiki's loft, where Paul goes to see Marcy, was a big deal. I’d recalled having shot a documentary in this second-floor loft in Soho at 138 Duane Street, just a big open space. It was the very first location that we showed Marty. And I thought, “Oh, this is perfect.” Then we showed him 30 other lofts, and he said, “OK, let’s go back to the first one.” It was a lesson: Don’t show the director the best location first. A woman lived there who was a downtown artist. We took it over and paid her money and moved her out. There was no back bedroom. We built the back bedroom where we shot Rosanna and Griffin.

Jeffrey Townsend: After Hours had no budget to build sets. It was a huge thing just to build the walls in Kiki’s loft to divide the raw, open space in slightly mysterious ways.

Rosanna Arquette: Kiki’s loft was so amazing. There was a skinny wooden staircase up and then the door opened to this huge space. What is that loft now worth, $10 million?

Jeffrey Townsend: To decorate Marcy’s room at Kiki’s loft, I sent my team out with the most confusing instructions. I said, “Get me 10 posters, and I do not care what they’re of. They need to have white borders or white backgrounds or white at the edges.” They bring back all these carefully chosen posters, and I hang them up with tape across the corners in the room, and then rage through the room and tear them off. So there’s just these little bits of paper still hanging. That’s what’s on Marcy’s walls. It makes the audience wonder, “What happened here? Who moved out in such a rage that they tore the posters down?”

Will Patton: As Kiki’s boyfriend, Horst, I was outfitted in some kind of leather bondage outfit and eyeliner. I remember Ellen Barkin visiting the set, and she came up to me and said, “Will, this isn’t you!” That’s probably why Scorsese cast me, because it was a little unexpected for me to be that sort of guy. The audience almost expects Horst to beat up Paul for abandoning Marcy, and then all I do is chastise him in a soft voice for his rudeness. The film plays on expectations. We expect one thing to happen, then it’s something completely different. Scorsese is so good at that, and it really keeps up the tension. It’s those “What the fuck is going on?” moments that are the funniest.

The sculptures

Nora Chavooshian (sculptor): To create the sculpture in Kiki’s loft that Linda Fiorentino is working on, Jeffrey Townsend and I talked about fashioning the form like Edvard Munch’s The Scream. The posture had to be a certain way so that when Griffin was holding the piece on his back later in the film it would almost wrap around him.

It was my understanding Scorsese wanted the sculpture to be paper mache because there are tactile, action-centric possibilities with the material, because it’s goopy and there are a lot of layers. This would also allow Griffin, toward the end of the film to be hidden inside this layered, goopy statue. I also had to cast a bunch of plaster of paris bagel-and-cream-cheese paperweights, which Kiki is said to make. I made a mold of an actual bagel and cast a bunch in plastic.

There was only one Kiki Scream sculpture, because that was such a detailed sculpture. The other major sculpture, the one in which June encases Griffin under Club Berlin toward the end of the movie, we had to do multiples because it was a breakaway. So Griffin had to sit for a body cast. We put him in a sweatshirt and sweatpants and padded it with foam so that once he was in the sculpture during the shoot, there would be a few inches all around him for him to move around and it wouldn’t be so claustrophobia-inducing.

After they wrapped principal photography, they were getting rid of the Scream sculpture. Amy [Robinson] sliced the hands off and gave them to me. I’m looking at them right now.

Club Berlin

Jeffrey Townsend: For the scene at Club Berlin, the punk club hosting Mohawk Night, we had been looking for what could be the actual dance club and separately looking for what could look like a basement that would be under a club with little daylight windows that somehow land you back outside. Rarely on a movie do you get a single location that can give you everything you need. We were tearing our hair out, and then all of a sudden somebody noticed this abandoned business at the southwest corner of Hudson and Spring. We tracked down the owner, got inside, and it had a giant bar in the center and the rest was just empty. With hearts beating fast, we found a doorway to the basement. And then in the basement we saw something I had never seen before: the basement went under the sidewalk and there was a manhole up to the street. The first order of business was to see if we would be allowed to mess around with a manhole in a sidewalk. The answer from the city was, basically, “Party on.”

Clarence Felder (“Bouncer”): Club Berlin was the perfect name for the place, because with all the chainlink fencing in the club and the guard posts outfitted with spotlights, it seemed like a divided city as Berlin still was at that time. To get into the place, you had to go through a path reminiscent of an escape route.

J. Hoberman (Village Voice film critic): There were those kind of crazy clubs in New York back then, but nothing like that in Soho. The Mudd Club, which was below Soho, would’ve been the prototype for Club Berlin. Places like that certainly existed. If the Mudd Club ever did something like a Mohawk Night promotion, it would’ve been completely ironic as opposed to terrifying.

Medusah: Griffin is in the club, and the bouncer says “Mohawk this guy!” and they shave a hunk of his hair before he gets away. I actually pre-shaved a spot on Griffin’s head and strategically left enough hair to cover the bald spot for other scenes.

Griffin Dunne: We were filming right in the epicenter of a scene in New York—a burgeoning art movement and hardcore punk music. A Bad Brains song plays in the club scene.

Rosanna Arquette: I wasn’t a big clubber or partier, but I went to the Limelight and those places once in a while. I went to a lot of the gallery openings. I was around Julian Schnabel. I hung out a bit with Basquiat; there’s a photo of us at a Jacksons concert. I knew Keith Haring through Madonna; she had this amazing motorcycle jacket on which he had done a painting on the back.

Valli O’Reilly: When we did the club shot, we didn’t have extra makeup and hair people, so we just had to recruit people who already looked like that. We’d go to all these punk clubs around New York on weekends to see what the various looks were.

Clarence Felder: I remember talking to a gentleman who had one of those reverse mohawks, with purple hair and green trim. I said, “Where do you work?” He said, “I have a job in a print shop, but they won’t let me be in the front. I have to be in the back.” I said, “What is the purpose of the presentation you’re doing?” And he said, “We’re the beautiful people.”

Jeffrey Townsend: Michael Ballhaus suggested a tower with a searchlight as a lighting idea. At that point Marty said, “I want to be the guy on the tower with the light.” Rita Ryack, the costume designer, outfitted him in a military uniform.

Jan Sebastian Ballhaus: Club Berlin was a very hot set full of smoke, which was especially difficult for Scorsese to deal with.

Clarence Felder: Mr. Scorsese was up on a camera platform. He had on a mask and an oxygen tank, so he wouldn't be bothered by the smoke.

Jeffrey Townsend: The motion lighting that you see is actually created by the dancers smacking hanging lights. The grip Stefan Czapsky invented what he called “slam lights.” It consisted of an automobile headlight welded to wires hanging from the ceiling just low enough that people on the dance floor could jump and hit them.

Cheech Marin: The basement below Club Berlin was a little like every New York apartment I've ever been in: small and cramped.

Griffin Dunne: The times I’ve seen the movie, every time Cheech and Chong drop through the manhole into the basement below Club Berlin, I get a smile on my face. I’ve worked with many actors, but they’re one of the few where I just sort of think in awe, “God, I can’t believe I worked with Cheech and Chong.”

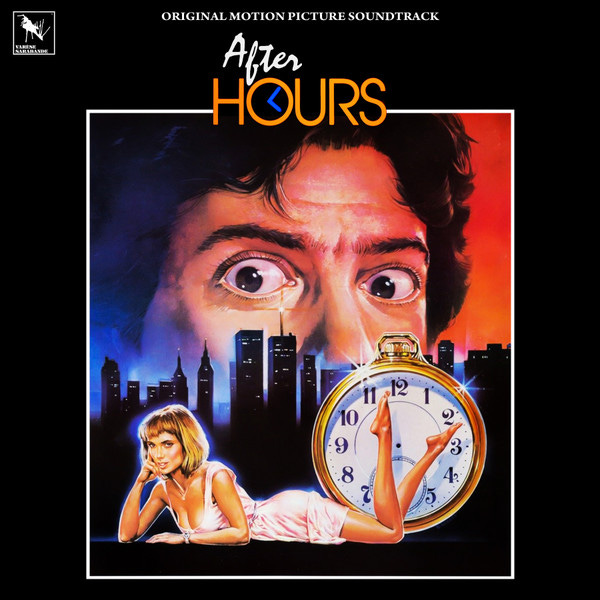

The music

Griffin Dunne: As soon as I was finished with my role as an actor, I was back to being a producer. I was in charge of securing the rights to the music for the film, so I was on the phone with music publishers or the artists, if I knew them directly, to get the cheapest price. We still hadn’t thought of a composer for the score. We had offices in the Brill Building, with our names stenciled in gold on the glass doors. Marty’s editing room with Thelma was there also. Down the hall from our office was the composer Howard Shore. We went over to his office, knocked on his door, and he was there making music with computers and synthesizers and stuff. He opened the door and was wearing a lab coat. Soon he agreed to come on and do the score.

Howard Shore: Marty and I were both working out of the Brill Building. I had moved there in 1980 after working on Saturday Night Live for a few years. Thelma was cutting After Hours with Marty on a different floor of the building. On the sixth floor, I had a studio, kind of like a lab, where I was working with electronic music. I knew Griffin Dunne and knew Marty from my work with David Cronenberg. But Griffin reintroduced me to Marty and Thelma for the score. I worked on it in the Brill Building, and we went back and forth from the editing room to my little electronic lab. I was using the Synclavier, a large computer system for digital music and an early sampler. On After Hours, I was composing very strictly to the film, creating pieces that synced exactly. Marty would come to my lab, and we’d listen to pieces and talk about them. I was principally using the Synclavier and delay effects to create the ticking-clock sound that’s woven into the score. It’s a little playful and kind of disarming, and there’s a bit of humor in it. It seemed to suit the film, because time is such a presence in the movie.

The premiere

Amy Robinson: After Hours had its New York premiere at the Museum of Modern Art.

Griffin Dunne: I went with my father. We were waiting for the limo to take us, and a battered Chevy Nova pulls up and the driver said, “Yeah, my limo broke down. This is my car.” So my dad and I arrived in this beat-up old Chevy Nova with children’s toys in the back seat.

Catherine O’Hara: I’m sitting there watching After Hours thinking: Who’s got the thing against blond women? Did you notice all the women are blond? Blondes must be very threatening. I’m a natural blonde, so I'm really threatening. [Laughs]

An accusation of plagiarism

Griffin Dunne: We were at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel promoting the movie, and I had just gotten a call from our lawyer, Jay Julian, that the radio monologist Joe Frank was going to sue, accusing After Hours of plagiarizing his work. I met Joe Minion for breakfast, and I said, “I have great news. We’re going to get sued.” He goes, “Why is that great news?” I said, “Because it means the picture is a hit. People come out of the woodwork to say, ‘I wrote that.’ It comes with every success.” And he goes, “Well, who’s suing us?” I said, “Some guy named Joe Frank.” He goes, “Oh, yeah, well, I know who he is.”

Joseph Minion: I had at one point definitely heard the Joe Frank short story “Lies” that he read on late-night radio, and details from it unfortunately wound up in the first section of the script, and I got walloped for that in every way imaginable. [Editor’s note: see 32:30 to 44:10 in the YouTube clip below.]

Amy Robinson: Joe [Minion] was a Columbia student when he wrote the script.

Griffin Dunne: Minion was just a kid. He thought that if he brought up the details that he had borrowed that the movie would fall apart. He wasn’t experienced enough to know that this could have been settled in advance.

Michal Story (Joe Frank’s widow): At the time After Hours was released, Joe got a phone call from someone who said, “Have you seen this movie? I think they’ve used some of your material.” He went to see it and was struck that a lot of the details from the beginning were taken verbatim: the plaster of paris bagel-and-cream-cheese paperweights, the money blowing out of the window of the cab, and the girl who tells a story of having been raped. Joe threatened to file a lawsuit, and the filmmakers settled for about $30,000.

Griffin Dunne: This was a terrible thing to happen at the beginning of the career of a writer like Joe Minion, who has one of the most unique voices in cinema. There’s no one like him out there. He’s a wholly unique individual, and the world needs more of him.