Quantum Criminals: a Steely Dan rogues' gallery

In their new book, Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMay see reflections of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen in the many characters from their songs.

When Alex Pappademas appears on the video conference screen, he looks like a bodacious cowboy who has just rolled out of bed. Slung around his shoulders is a serape that no one would mistake for a spangled leather poncho, but the brightly patterned blanket is serving him well on this chilly morning in Los Angeles.

“It is apocalyptically cold in my garage today,” the prolific writer and podcaster explains, “so I’m dressed as the Gaucho.”

“It’s the Major Dude himself!” says the artist Joan LeMay, greeting Pappademas from her home in London. “I love the look. It makes me incredibly happy.”

Expanding Dan is a reader-supported publication. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription. You’ll never miss a post and will have full access to the archives, including the oral history of recording with Steely Dan.

These are precisely the sort of pleasantries one would expect to be shared between two people who’ve spent the past few years immersed in the collective life and work of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen—in particular the many and various characters who inhabit the songwriters’ fictional worlds. Fresh from their studies deep within the proverbial Caves of Altamira, Pappademas and LeMay have emerged with the remarkable Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan, which will be published by University of Texas Press on May 23.

In the classic rock literary canon—among innumerable volumes on Dylan, the Beatles, the Stones, Zeppelin, and so on—the Dan shelf is conspicuously sparse. The most bookish band of them all has somehow yielded the fewest books. Nearly 30 years after its first printing in 1994, Brian Sweet’s Reelin’ in the Years remains the most complete Steely Dan biography. Don Breithaupt’s 331/3 edition about Aja, from 2007, gave us the closest analysis of the mechanisms underpinning Becker and Fagen’s compositional genius. Barney Hoskyns’s 2018 anthology Major Dudes collected some of the finest interviews and criticism published over the years.

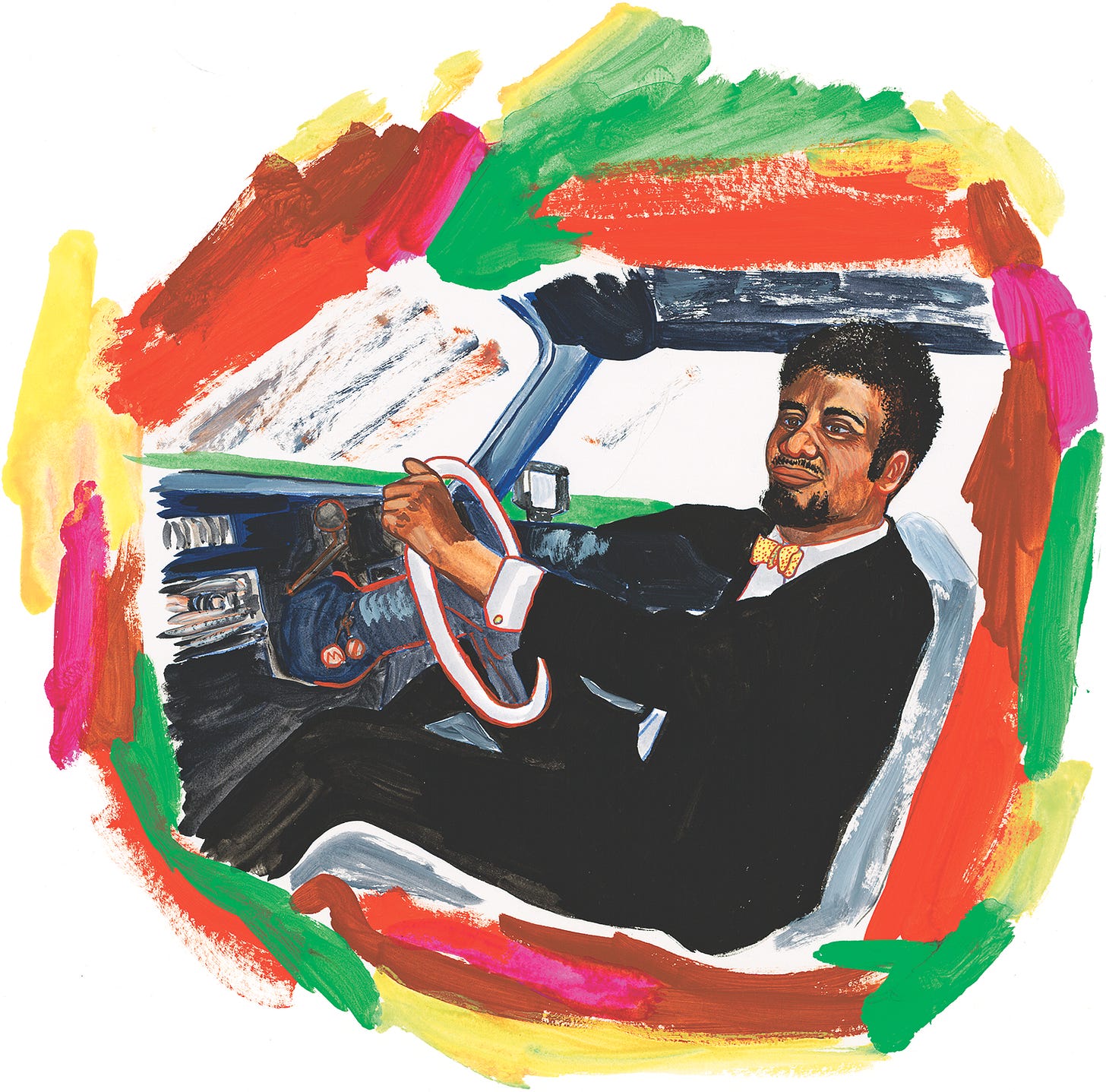

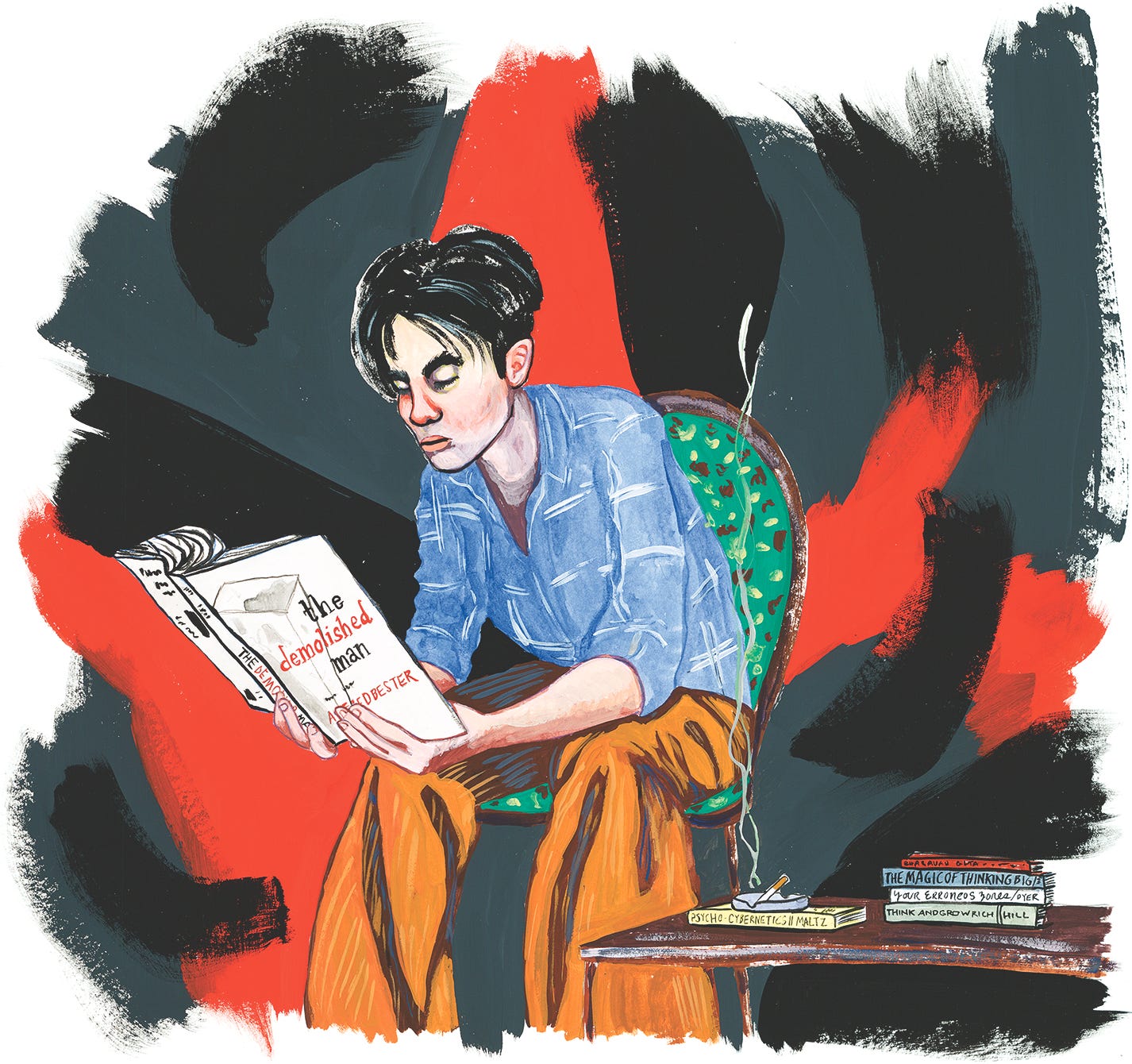

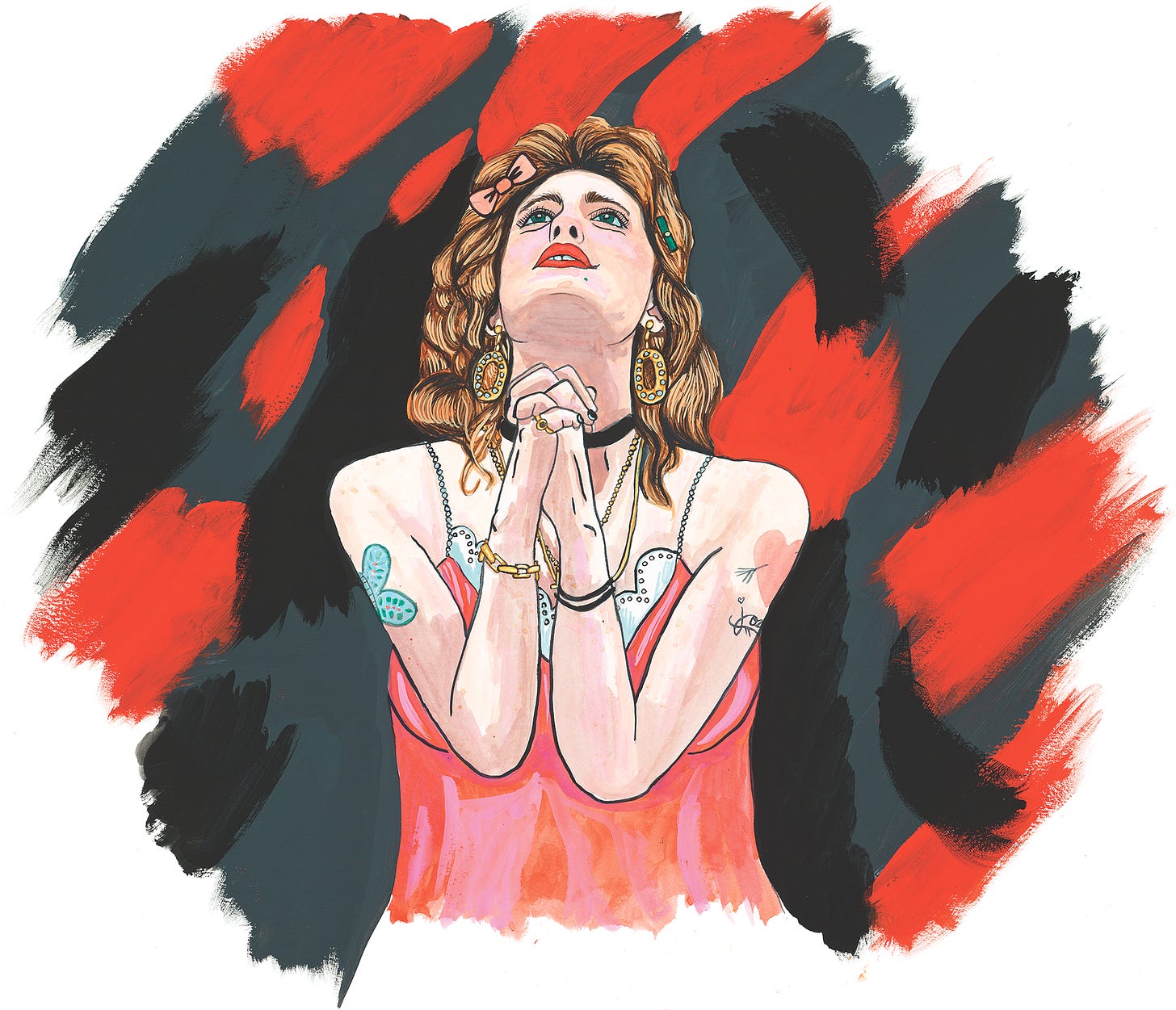

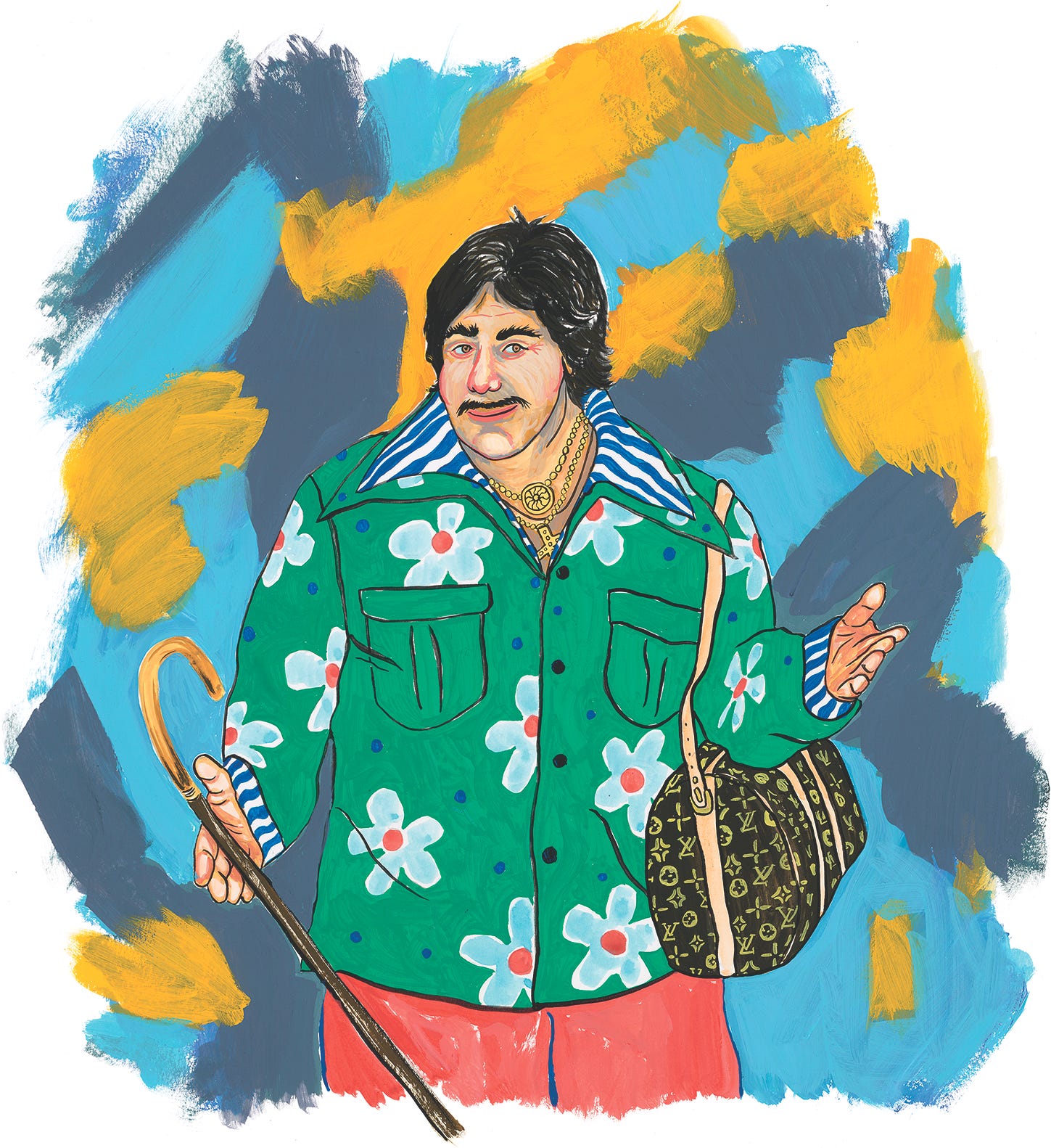

With the addition of Quantum Criminals, we finally have a book about Steely Dan in which the writing and art fully measure up to the sophistication and beauty of Becker and Fagen’s music. Each chapter ingeniously ties an essay to a character or group of characters related to a song, from Jack of “Do It Again” to Dave from Acquisitions of “Everything Must Go.” Pappademas’s incisive, elegant prose poetry pairs perfectly with LeMay’s colorful hand-painted portraits that offer humorous and empathetic glimpses of the Dan’s menagerie of luckless pedestrians.

The book’s title is derived from Becker’s droll explanation of being hit by a taxi in New York during the troubled recording of Gaucho. “We were quantum criminals,” he told The Independent in 1994. “The car and I were attempting to occupy the same place at the same time.” Pappademas says he was drawn to the phrase, which sounded to him like the name of a long-lost Steely Dan song. “And in this context, it works as a description of the characters,” he says. “There are plenty of actual criminals in this book, from Nixon to Jive Miguel, but also everybody in it is an outlaw in some spiritual or cosmic way, a violator of the laws of the universe, on the lam from something or someone.”

Throughout the history of Steely Dan, Becker and Fagen reflexively distanced themselves from their characters, frequently warning journalists not to conflate them with the narrators of their songs. One of the things that makes Quantum Criminals so exceptional is Pappademas’s inclination to look for the reflections of the creators within their creations. He follows bread crumbs, connects dots, careers down rabbit holes into uncharted interpretive territory where other writers may have feared to tread. And he comes away with a wealth of compelling conclusions. Not just about the meaning behind songs that have perplexed generations of loyal listeners, but also about the mystery that lies at the very center of Steely Dan: the nature and evolution of the Becker-Fagen creative marriage.

Earlier this month, I talked to Pappademas and LeMay about becoming intimately acquainted with Steely Dan’s fabled fools, Becker and Fagen’s unsung compassion for deluded people, and why the Dan has become the soundtrack for our tumultuous times.

Is there any artist in the history of rock whose songs include more characters than those of Steely Dan? Bob Dylan occurred to me. But his characters seem like they’re viewed at a glance as the song speeds down the highway.

Alex Pappademas: Bob’s characters are like Robert Altman characters—they go past the camera, and you hear them having a conversation, but they’re just there to be in the mix of the whole thing. Warren Zevon has some Guys. But it’s hard to think of anyone who rivals Steely Dan. It’s part of the death of proper names in pop music. At some point everything became “you” or “I.” There are a few exceptions, such as in hip-hop. But even then, there are not too many characters other than the self and shifting personas. For example, Drake songs are not about all these women that Drake is talking about, which might actually be interesting. They’re about Drake and how he feels about them, and you see them exclusively through him. So I don’t know that there is any artist that would be more appropriate for this kind of book. The Beatles, I guess. You’ve got your Eleanor Rigby and your Sgt. Pepper and all of that. But you almost have to take the Beatles off the table in every conversation about rock music.

Becker and Fagen would tell journalists not to try to read their songs as veiled personal narratives. The most they would allow was that “Deacon Blues” was the closest they got to autobiography. One of the things I enjoy about Quantum Criminals is your willingness to go beyond what they were willing to say. In your analysis of “Midnite Cruiser,” for instance, you write, “Walter was Donald’s bohemian muse, and their collaboration was a platonic love story. … Walter gives Donald the permission to become the thing he’s supposed to become. Walter, in other words, might be the real Midnite Cruiser—the gentleman loser Donald’s always wanted to shake his suburbanness and become.”

Alex Pappademas: That’s one of the assertions from the book that feels the most like a fan theory. Everything that’s in the book, I assume, Donald might take issue with. A lot of it is speculative. It’s rock criticism. We’re out on some limbs in all of this. One of the threads in the book is thinking about Steely Dan in terms of Black music and Walter and Donald’s relationship to Black music. And “Midnite Cruiser” is their first and maybe clumsiest of songs about that identification. “Deacon Blues” is the other end, with them having come out the tunnel on the other side of it fully identified and also making a joke and a tragedy out of that identification. “Midnite Cruiser” is the earliest attempt, and it feels very adolescent. It’s a reaching for that identification with Black music and Black musicians: “Can’t you see I’m not like these other white squares around me?” People around Steely Dan often say in interviews that they didn’t know what Walter did. But it seems Walter created some permission for Donald to be a different songwriter. Walter brought some edge that the songs otherwise wouldn’t have had. Walter was a little further out there. And there was a little bit of something in that friendship where, if you were Donald and accustomed to identifying with a jazz guy who’d lived this crazy life, Walter is the guy who’s really doing it. That’s not to say that in the 1970s music scene it was hard to know somebody who had a drug problem. You didn’t have to look far to see somebody taking risks in that way. But I think that’s what’s going on in that collaboration. Donald would probably hate this idea and reject it, but they rejected everything. There was a general “do not explain” policy.

Joan LeMay: Part of what’s so much fun about Steely Dan is the fact that everything is ridiculously oblique intentionally. It leaves a lot of room for interpretation. Like, I painted the El Supremo [from “Show Biz Kids”] as a sad dude in a stained shirt on a chair. Someone else would probably picture him differently.

With regard to your portraits, Joan, most of the characters look like contemporary people who we might see around the way.

Joan LeMay: Some of them were meant to be timeless around-the-way people, some of them were ’70s or ’80s people. Lots of the people depicted are based on actual real people. These were painted in lockdown, so I didn’t have people to pose for me. I had friends send in photos of themselves, used a lot of found photos, and did a lot of posing myself. And there were some real-life figures mentioned in the songs that I’d never seen. For instance, Cathy Berberian [from “Your Gold Teeth”].

Alex Pappademas: She looked incredible. The mumus!

Joan LeMay: Yeah, wow, what a tremendous human to have existed in the world.

Alex Pappademas: The clothes on Owsley Stanley [from “Kid Charlemagne”] look like an outfit somebody made from a Butterick pattern from the ’70s.

Joan LeMay: I often looked at ’70s fashion catalogs and sewing manuals from thrift stores for outfit ideas. The bottom half of the Owsley Stanley outfit is based on my friend’s uncle Nico, who’s a wine salesman in rural Oregon. Everything is from somewhere!

Steely Dan fans hold specific, personal ideas about the characters from the songs that they may not want disturbed by an artist’s interpretation. Did you worry about putting faces to these names?

Joan LeMay: I absolutely thought about that. People are definitely going to go, “No, I’ve had this idea in my head of who Cousin Dupree is, and that ain’t it!” We all walk around with a general idea of these characters in our heads. It’s almost like a dream, where you see a blurry face and figure. The challenge for me was: How do I visualize that?

Alex Pappademas: I liked the idea that you weren’t necessarily saying, “This is definitively what this character looks like,” but you were casting a person in that role, almost like a stage play. From a writing standpoint, I had the same concern, and that’s why, pretty early on, I discarded the idea of writing fiction. For instance, I tried to write an Elmore Leonard–style story about Jive Miguel—you know, he’s in from Bogota. Whether it was qualitatively bad was up to somebody other than me, but it was too much. There are some books of noir stories inspired by Steely Dan songs, and I always hate them. It’s not the fault of the people who want to do them, because I understand the impulse of thinking that would be cool to do. And some people might even really enjoy reading them. But I decided pretty quickly that if I was gonna fill the gaps with anything, I was gonna fill it with speculative rock criticism. Because what I like about the portraits is that they don’t feel like they are necessarily trying to pin it down. It’s almost as if Joan has taken these contemporary people and posed them in the style of classical portraiture.

Joan LeMay: I love that you said “casting,” because the image folder I had on my computer was called Dan Casting Gallery. I would troll through a million things and say, “Oh, this looks like a Dan Universe person” or “Oh, that’s Snake Mary [from “Rose Darling”]! She’s got the part 1,000 percent!”

Alex, you were initially inspired by a book about Liz Phair?

Alex Pappademas: It’s called The Last Rock Star Book: Or: Liz Phair, a Rant. It’s by this great ’90s rock critic who wrote under the name Camden Joy. He was famous for putting up a series of wheatpaste posters during the CMJ music festival in New York. The posters had the feeling of protest, but you were never quite sure what was being protested. He was ahead of his time. He was like the Hipster Runoff of the ’90s. He is just an incredible writer and a one-of-a-kind music journalist. Partly inspired by that book, I wrote this confessional autobiographical thing that was gonna be the intro to the Steely Dan book. It was much more about the stuff that this book isn’t about, which is my own experience, the role that the music played in my life at a certain time. It was this whole thing about me and my friends being unsavory characters ourselves, doing drugs and listening to Steely Dan, and me getting broken up with and stuff. I ultimately decided it was too personal to put in the book.

There was a point in writing Quantum Criminals where I was trying to take in different influences. At one point, I purged my bookshelves of everything I felt comfortable with. So if I was turning my head, I would see things that were not the references that I normally saw while writing. It was an attempt to reboot psychically. I’m not sure how much of that ended up in the book. I don’t know that I can claim that I’ve even read Madness and Civilization by Foucault, but it would be funny to say that through that book is how you decode everything that’s in Quantum Criminals: “It all comes from ol’ Michel!” [Laughs] But no, Camden Joy was a big one. Also, Joe Carducci. I can make you a list of what I actually had on hand, but a lot of it would be really pretentious. Witchcraft U.S.A. [by Florence Hershman]—that was a big one. [Laughs] Let’s feed the fake news ecosystem and just be like, “These are my influences.”

How did you both originally get into Steely Dan? Alex, you write in the book about ironically buying a copy of Katy Lied in the 1990s.

Alex Pappademas: Yeah. Cut to me, 25 years later, writing a whole book about Steely Dan! [Laughs] I was in college in Boston, so it was the late ’90s—’97 or ’98, something like that. I remember everything I bought that day. And I’m not one of those people who remembers that kind of thing. I got Givin’ It Back by the Isley Brothers—a very good ’70s covers album that has their version of James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain” on it. Quiet Nights by Miles Davis—it’s the Brazilian album, which Miles hated. And there were one or two other things. To round things out I bought Katy Lied out of the dollar bin. I was curious about it because the Minutemen had covered “Doctor Wu.” But also I was thinking, Wouldn’t it be hilarious if I bought a Steely Dan record? Which is silly because records don’t know when you’re buying them ironically. Dumb 20-something me listened to Katy Lied and thought, Isn’t it funny that I’m listening to this smooth music instead of the cool, edgy music I’m supposed to be listening to? Joan, you grew up on this stuff, right?

Joan LeMay: Steely Dan is my very first musical memory. My parents had very few records when I was growing up. Among them was the Steely Dan catalog, plus [Donald Fagen’s 1982 solo album] The Nightfly and Carole King’s Tapestry and Linda Ronstadt albums and Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick, which was often playing. Huey Lewis and the News’s Sports joined the fray at a certain point. I remember pulling out Can’t Buy a Thrill and liking it the most because it was the craziest cover. I flung it on the turntable, which was high up in a cupboard. From then on for me, it’s always been the Dan.

In the book you posit some theories about the cause of what you call “the Danaissance.” Ultimately you settle on the idea that people today gravitate to Steely Dan because, as you write, “our fast-warming world is more Dannish than it’s ever been. Donald and Walter’s songs of monied decadence, druggy disconnection, slow-motion apocalypse, and self-destructive escapism seemed satirically extreme way back when; now they just seem prophetic. We are all Steely Dan characters now. Citizens Dan, living in an age of malaise and disillusionment as pervasive as the fog of failure enveloping Gaucho’s fabled fools.” Can you talk a bit more about the notion that Steely Dan is the band for this particular moment in history?

Alex Pappademas: Maybe every generation feels like they’re living through the collapse, the real downfall of America. I talk to my mom about the ’60s, and she’s like, “We were convinced that they were gonna round all of us up.” There was that feeling back then, and I probably felt like that in the ’90s. And now it’s interesting to be like, “No, this is really it.” It may be a permanent feeling. But I don’t think it’s a coincidence that people have fully embraced this music from the Carter administration years at this moment when it feels like everything is really sinking into the sea, that America is collapsing in a lot of ways. What is outside the margins of all the stories in Steely Dan songs is this feeling that everything is going to shit. Donald and Walter were pretty cynical about the ’60s as it was happening. And you sense it in a song like “Change of the Guard”—a pop song about everyone getting together and things getting better. Some people might have sung that sincerely and believed it, or wanted to believe it or manifest it. And I think Donald and Walter were just like, “Isn’t it funny that we can write a song like this?” What they’re really seeing, I think, is almost an interpersonal apocalypse, where the ’60s are about this idea of coming together to use psychic energy to levitate the Pentagon or whatever, and then the ’70s come along, and all of the freedom is still there, but there’s no sense of obligation to each other. The disillusionment and jadedness and hopelessness that breeds seems very familiar to me. When you open Twitter, it’s those voices that are wailing at you. But I also think everybody feels like their time is the most fucked-up time there has ever been. And Donald and Walter were absolutely just brutal social satirists of their moment. Steely Dan’s lack of sentimentality and refusal to put a nice face on things except in a super-ironic way was what a lot of punk aspired to be.

Joan, what Alex was just saying made me open the book and turn to your portrait of the Third World Man—the man in the tinfoil hat, who might be seen these days at a MAGA rally.

Joan LeMay: He’s the archetypal Guy with a Sign who wants to tell you that the end is coming. He wants to be fanatical about you understanding that he understands what’s going on. He’s passing out whistles right now at the Marjorie Taylor Greene rally.

Alex Pappademas: When I was a kid, there was a guy who used to drive a van around San Francisco. There was a lot of fine print on the van. I recall he believed that John Lennon’s real killer was not Mark David Chapman but Stephen King. That was the core of his belief system.

The phrase third world man is one of those things in a Steely Dan song that sounds common but you’re left wondering, What does that actually mean? Our country is predicated on the idea that we are the first world, that there is another world in which conditions are different, and we will never be subject to the conditions of that other world. And I think the song “Third World Man” is about the fragility of that boundary. But it’s also the end of the ’70s, people are going crazy at random, and somebody might just burn down their own suburban home for no reason. The center just does not hold.

While we’re talking Gaucho, in your essay on the album’s title track, you write, “I’ve never been able to hear the song as anything except Donald singing to Walter, reminding him of what they had and what they stood to lose, trying to call him back from some cliff’s edge.”

Alex Pappademas: OK, I think that’s actually the most speculative thing in the book. I’m speculating anytime I’m getting into the nature of Walter and Donald’s relationship, because that was the thing that they were the most opaque about. I’m probably sentimentalizing it a bit and probably reading it romantically, but how did they arrive at this story that’s about vexed love between two men? There’s a part in the essay on “Through With Buzz,” where we talk about how everything’s a love triangle when it comes to Steely Dan. There’s always a third problematizing a relationship—whether it’s a person or drugs or something else. And “Gaucho” I imagined as these two guys who are on the verge of a great success, they’ve got heavy rollers, something’s about to happen for them. And I do feel like after Aja, that was the feeling for Donald and Walter. They’d had some hits, but Aja was this huge phenomenon, and they were trying to follow that up with something even greater. It’s at that moment that Donald loses Walter to drugs. But the thing is: Who the fuck knows? They haven’t confirmed or denied, and they never will. They’ve only obfuscated. That created a lot of creative blue sky for this book—a lot of room to imagine things. In an early draft, I was saying “I think” too much, and it felt like I was couching. Obviously all of it is what I think. And at a certain point, it felt more fun to make the big swing and claim the big thing that I’ve always heard in the music. I do this also with Beatles songs, especially those from Let It Be. I’m always thinking about that record as John and Paul talking things out, having a conversation in music. Becker and Fagen are as important to me as Lennon-McCartney, and I’m interested in the nature of their relationship as it plays out in the music, in what can be heard if you listen to these songs as scenes from a creative marriage. And Gaucho is where that reading becomes the most plausible.

Even the song that is erased before it can be included on Gaucho, “The Second Arrangement,” is about infidelity.

Alex Pappademas: Yeah, it’s a guy who has something else going on across town. Everybody on Gaucho is like, “This is great. This lifestyle is really going well for me, and I’m really feeling good about it.” The narrator from “The Second Arrangement” is basically like, “There is nothing depressing about what’s happening right now.” He’s making it sound sexy and cool to have his laundry in the trunk, when in reality that would be extremely stressful and hard and spiritually taxing—and also ethically problematic if the two people don’t know about each other.

When you sit back and consider the range of Steely Dan characters you’ve gotten to know so intimately while making the book, are there some features all of them share?

Alex Pappademas: Thinking about this catalog as a whole, what I come away with is the feeling that it belies Donald and Walter’s reputation as these cold bastards who took nothing seriously and cared for no one. There’s a lot of empathy for deluded people in these songs and a keen understanding of how we all build architectures of delusion just to get through the fucking day. We imagine ourselves as something we’re not or imagine our situations as better than they are. That’s probably not what you think you’re gonna get from Steely Dan when you drop the needle on the turntable or when it comes on classic rock radio. It’s not what they're famous for. But for me the through line is the empathy, the kindness of Steely Dan for all these poor devils laboring, struggling, telling themselves lies. There are songwriters who would have said, basically, “Look at these idiots.” And as much as Donald and Walter were really look-at-these-idiots guys in interviews and projected that as their way of being in the world, they wrote in a very different way. That’s what I appreciate more, having spent as much time with these songs as I have.

In line with Becker and Fagen’s compassion toward their characters, Joan, there’s not much pointing and laughing in the way you’ve rendered them in your portraits.

Joan LeMay: Certainly not. I was interested in the deep humanity of these characters. The undercurrent throughout seems to be the inescapability of human fallibility. We are all these characters in some way, and you end up loving them and seeing the difference between how they present themselves and how they actually are. Is there anything more relatable than self-delusion? Like, in the portrait for “Lunch with Gina,” Gina looks as exasperating as she does exasperated. She’s eating this shitty salad and looks like she’s not gonna shut up. But also you’re like, “Oh, this poor woman. She needs to vent. She just needs someone to talk to.” It’s deeply relatable.

Alex Pappademas: God bless Donald and Walter for never explaining anything, and leaving it for all of us to figure out.

Yes I’m looking forward to reading the book….

I’d always thought the reference to “hard times befallen” in Hey 19 was to a one hit wonder band called the SOUL Survivors (Expressway to Your Heart”…….I could be totally wrong.

After all, you may get lucky in the music business for a few good years…..

Can’t wait to grab this book