'This is the middle-aged White-guy Wu-Tang Clan'

Music journalist Steven Hyden discusses working on the film Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary.

Is Steely Dan yacht rock?

The debate has raged in the two decades since the Yacht Rock web series coined the term for a subgenre of smooth, slickly produced music that flourished from the mid-1970s until the mid-’80s.

“If you go back to the original definition of yacht rock the way that the Yacht Rock web series creators define it, which is pop-rock music that is influenced by jazz and R&B, Steely Dan certainly falls under that umbrella,” says the music journalist Steven Hyden, who served as story producer of the new film Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary, an affectionate, compulsively watchable 96-minute survey of the genre, which premieres November 29 on HBO.

Among the film’s talking heads who make a compelling argument for Steely Dan’s inherent yacht-ness is the erstwhile AllMusic critic and Yacht Rock series host “Hollywood” Steve Huey. He calls Walter Becker and Donald Fagen’s musical project nothing less than “the primordial ooze from whence yacht rock sprang.”

But at least one person remains unconvinced. When director Garret Price called Fagen to request an interview, Mr. Steely Dan offered a rather colorful kiss-off before hanging up the phone: “Why don’t you go fuck yourself?” (A recording of the brief encounter is included in the film.) And yet the soundtrack is peppered with Dan cuts: “The Caves of Altamira,” “Reelin' in the Years,” “Bad Sneakers,” “Black Friday,” and “Peg.” (Presumably the licensing fees were handsome enough to overcome Fagen’s allergy to his life’s work being classified as yacht rock.)

Those who believe only a fool would say that Steely Dan is yacht rock wonder how anyone could reasonably associate a pair of downer surrealists such as Becker and Fagen with the likes of Kenny “Footloose” Loggins and Christopher “Sailing” Cross, both of whom are interviewed in the film alongside the Yacht Father, Michael McDonald.

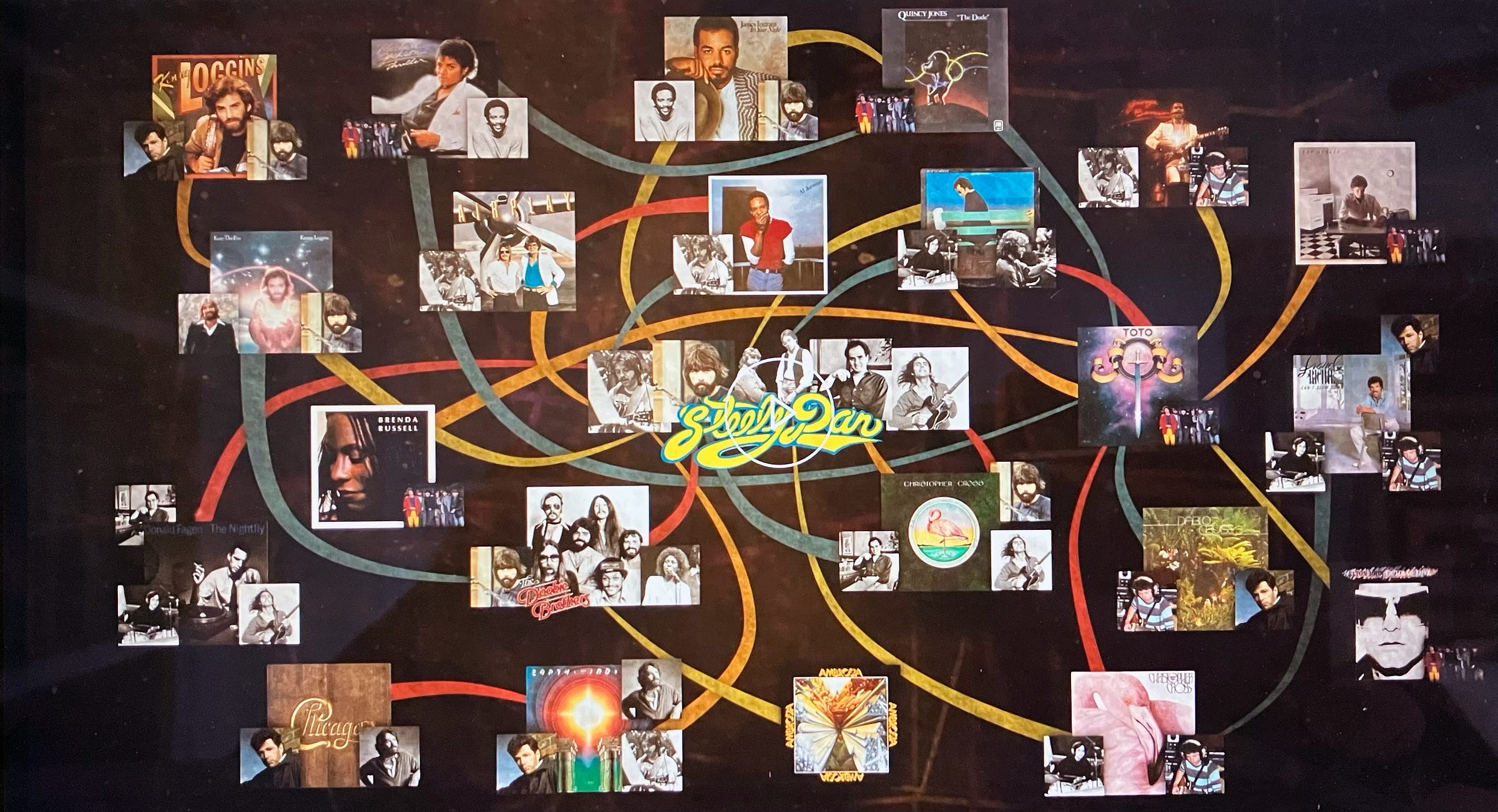

“Any time Steely Dan fans get mad at us online that Steely Dan isn’t yacht rock, the artist they most want to be disassociated with is Christopher Cross, because they don’t think he has anything to do with Steely Dan,” Huey says in the film, which is coproduced by Madison Cross, Christopher’s daughter. “But that means they’re not reading album credits. Christopher Cross’s albums were produced by Michael Omartian, who did a lot of arranging and piano work for Steely Dan. He’s got guest spots from Larry Carlton. He has guest work from Jay Graydon on guitar as well. And, very important, he’s got backing vocals from Michael McDonald.”

“In the movie,” Hyden tells me, “we make the case that Steely Dan were the band where some of the yacht rock artists got started,” among them McDonald, drummer Jeff Porcaro, and keyboardist David Paich. “Or they were, in some way, Steely Dan adjacent. Someone like Christopher Cross, for instance, didn’t appear on any Steely Dan records, but he was inspired by Steely Dan, emulated what they did on records like Aja, and ended up taking it to a different place. The idea is that without Steely Dan, a lot of this music might not have happened, or at least it wouldn’t have happened in quite the same way.”

What separates Becker and Fagen from the typical yachtsmen, Hyden acknowledges, is their lyrics. “The wit and the cynicism of Steely Dan is really nowhere to be found in the music of Michael McDonald, Toto, Kenny Loggins, and Christopher Cross, and that is an important distinction,” he says. “Still, there’s more than a little bit of shared DNA going on with all these records, and that shouldn’t be overlooked.”

Tabling the age-old argument for a moment, Hyden and I moved on to other topics: the “nyacht” rock of Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles, why yacht rock is “the middle-aged White-guy Wu-Tang Clan,” and the broad demographic appeal that has helped the music endure.

You might also enjoy…

What do people most often get wrong about yacht rock?

What happens a lot is people using yacht rock synonymously with soft rock. Even the SiriusXM Yacht Rock Radio station plays songs by Air Supply and Chicago and things [that aren’t yacht rock]. With this movie, we were really trying to nail it down to what the Yacht Rock guys were referring to, specifically, which was this group of musicians in L.A. in the late ’70s and early ’80s who knew each other and collaborated on each other’s records, how they came from the pop-rock world but were influenced by R&B and jazz. That’s what we focused on in the movie. The issue typically has been treating yacht rock as another term for soft rock music from the ’70s. [Yacht Rock host] Steve Huey says in the movie, “All yacht rock is soft rock, but not all soft rock is yacht rock.” That’s an important distinction to make.

Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles come up as examples in the film of bands often erroneously lumped into the yacht rock genre. But Fleetwood Mac are missing the jazz element, and the Eagles are a country-rock band.

I think the one yacht rock song that the Eagles have is “I Can’t Tell You Why.” It’s a little bit more R&B, with the prominent Fender Rhodes. But just using yacht rock as a catchall to describe any music from California in the ’70s or any kind of mellow band from the ’70s is not correct. From the Steely Dan side, you see people object to the term yacht rock. Some people get really testy about it. And this is addressing your readership: Steely Dan fans who maybe are thinking that the movie is just going to be talk about soft rock and jokes about boats and stuff—I mean, the movie’s a lot of fun, and I think the movie’s funny, but it does not treat the music like a joke. The humor comes organically out of the musicians who are just really funny, cool guys. They’re all likable, and they’re all self-aware, too, which is always an endearing quality. So it’s a fun movie, but it takes the music seriously, maybe in ways that other examinations of this scene haven’t.

The film seems to find its thesis in something that you say about the jokey, cartoonish image yacht rock has taken on in some corners, with cover bands smirking on stage in matching captain hats and so on. You believe the perception of yacht rock as a kind of joke has altered the way the music is perceived, or that it has obscured the actual story of this scene.

On the whole, yacht rock as a term has been a positive for these musicians because it did identify that this was a scene. That wasn’t appreciated as much before the web series. But even the web series, in a way, has also been distorted a little bit by time. People think of the web series as just being this sort of jokey thing about the musicians. But you hear from Steve Huey and [cocreator and star] J.D. Ryznar in the movie a lot, because they know a lot about this music. They approach it from an almost scholarly perspective. Steve Huey is a music critic. He has hundreds if not thousands of bylines on AllMusic. J.D. is a comedy writer, but he is an amateur historian of this music. I knew they’d be articulate, but I didn’t know that we’d end up using them quite as much as we did. I quickly realized it’s relatively easy to find people who can talk about Steely Dan. However, there weren’t many people who could go deep on Kenny Loggins or Christopher Cross. Only Steve and J.D. could do that. They have studied this music. They looked at liner notes and figured out organically that not only were these musicians all in the same place at the same time, but they were playing on each other’s records. At one point early in the making of the movie, I was outlining the story with Garret [Price, the director], and I was like, “This is the middle-aged White-guy Wu-Tang Clan.” You’ve got Christopher Cross and Michael McDonald over here on this one record together; you have Michael McDonald and Kenny Loggins over there on another record. Michael McDonald is the center of this. He’s the common touchstone that links everybody in the movie, because Christopher Cross and Kenny Loggins didn’t really associate, and Loggins didn’t do things with Steely Dan. But they all did something with Michael McDonald. He’s the central hub.

The super connector.

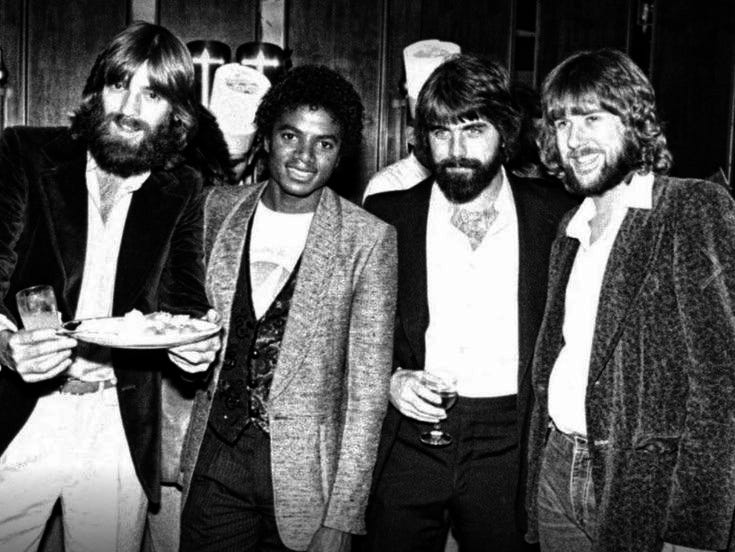

In the L.A. studio scene in the ’70s, you had this group of musicians who were basically just hanging out in studios during the week. You’d do a session at one studio in the morning, then go do a session at another studio in the afternoon. And people like Steve Lukather and Jeff Porcaro and David Paich were playing on records that we all know that they played on, but they also played on records that they weren’t identified as being on the record. And a lot of times they were records that maybe the artist or record company wouldn’t have wanted to publicize that the members of Toto were playing on it. Back then you had musicians that were playing in all different genres and with all different kinds of artists, whether they were in rock or R&B, whether they were White or Black—it didn’t really matter. These guys were so good, they could play anything. What’s interesting to me about that is that it really cuts against the grain of how we talk about music a lot of the time, which is trying to put things into specific genres or even specific demographic groups.

We talked to some younger musicians for the movie, and when they look back on that studio era, they expressed a lot of longing for that time. We live in an era now where a lot of artists can’t afford to go to a great studio, so they’re recording at home and sometimes they’re playing all the instruments themselves on their records. There’s a positive aspect to that because it democratizes the making of music; you don’t have to spend millions of dollars to make an album anymore. But part of the appeal of a record like Aja is that it is a showcase for world-class musicians playing amazing songs in a world-class studio, and everything is world class. It’s hard to achieve that now.

There’s a scene in the film when director Garret Price calls Donald Fagen to request an interview, and Fagen says, “Why don’t you go fuck yourself?” I wasn’t shocked that Fagen wouldn’t want to go on camera to discuss yacht rock, but were you or the other filmmakers surprised at all by the intensity of the rejection?

Well, here’s what I’ll say about this. Do I think Donald Fagen has felt some annoyance over the years about being associated with yacht rock? Yeah, I do think that. Do I also think that in that particular scene that he’s maybe exaggerating his annoyance a little bit for comedic effect? Yeah. That’s just my interpretation of the scene. The reason I make that interpretation is that there are Steely Dan songs in the film. Do you really think he was that upset if he agreed to let us use the songs in the film? Do you really think he was upset if he called Garret and then allowed himself to be recorded? It would’ve been easy for him to just say no or ignore our requests altogether. We also had to deal with Irving Azoff, Steely Dan’s manager, and it’s not like he’s known as Mr. Warm and Fuzzy, either. Those are two pretty tough cookies there. So the fact that there’s all this Steely Dan music in the film—my feeling on that scene is that it’s not quite what it seems. I think Donald Fagen is a self-aware person. He’s been known to dabble in irony from time to time, we can all agree. So my interpretation is that phone call is Fagen going into Larry David mode.

He’s playing up the character of Donald Fagen, curmudgeon.

Right. It’s not like we ambushed him. Just to get him on the phone, we had tried for a long time. I can’t speak for Fagen, but I think when he got on the phone with Garret, he knew what he was doing.

So the clip of the call that appears in the film wasn’t a recreation? Because I’ve listened to that segment several times, and maybe it’s simply the quality of the recording, but it doesn’t sound like Fagen’s voice.

No, that’s his voice. That was the phone call. Donald Fagen was the white whale for this film, without a doubt. Not only for the interview but for the music. I wasn’t directly involved, but I know that it was a long, protracted conversation just trying to get the Steely Dan music. Obviously we wanted to talk to Fagen too, but I was always operating under the assumption that he wouldn’t do the interview while still hoping that we would at least get the Steely Dan songs in the movie.

It would’ve been so easy for Fagen to not be involved at all. If he really hated the idea of the movie, he could’ve just not responded or said, “No, you can’t use my music.” So for him to say “go fuck yourself” to the director was kind of perfect, really, because what else is he going to say? Maybe that’s all he needs to say about it.

While you didn’t land Fagen, you did get longtime Steely Dan producer Gary Katz to sit for an interview, and he helps flesh out the Becker-Fagen story.

Right. And it’s not like this is a Steely Dan movie. They’re an important part of the story, but they’re not necessarily the focal point. They come in at the beginning and the end. Just speaking for myself, I didn’t really expect Fagen to agree to an interview. My hope was more that he would allow us to use Steely Dan songs, because I think the movie would’ve worked without it, but it would’ve been diminished. Having the Steely Dan songs in the movie is not only illustrative—we talk about the songs, and we actually talk quite a bit about “Peg,” both at the beginning and the end—but it also just makes the movie more fun to watch because it’s great music. And one of the things about this doc is that it’s pretty much wall to wall music. It’s a fun excuse to immerse yourself in this music for 96 minutes.

“Peg” is also a convenient narrative through line. The song illustrates the meticulousness of the late ’70s studio era, then allows you to introduce hip-hop’s fascination with yacht rock as De La Soul samples “Peg” on “Eye Know” in the late ’80s.

[De La Soul producer] Prince Paul refers to “Peg” as a “hood” song. He says the reason why De La Soul wanted to sample Steely Dan is that it was a fixture of their childhood. It wasn’t something that they had to come back around to. They always loved it. One of the things I find really interesting about this story is how yacht rock had its moment commercially, then it went away, and then it had this comeback in the 2000s. But it’s really the White audience that went through that arc. The Black audience never really abandoned these guys. It’s an interesting spin on how detractors often talk about yacht rock, which is as this sort of white-bread music. And I feel like this movie pushes back against that. In the film Questlove talks about how Michael McDonald has always had a strong Black following. It is not just White people in the suburbs who were listening to this music. The reason why it endures is because it has this broad demographic appeal, and in a lot of ways, the Black audience was more loyal to these artists than the White audience was. The White audience was the one that had to be brought back around in the 2000s with this web series.

They had to be reeducated.

Yeah, exactly. It feels like the appreciation that was coming from Black music fans or Black artists was never ironic. It never went into the irony zone the way it did for a while with the White audience.

When I interviewed Peter Gunz, he said the same thing about sampling Steely Dan’s “Black Cow” for “Deja Vu (Uptown Baby).” Aja was an album he and Lord Tariq had in their collections growing up alongside R&B and funk albums, and so it just seemed natural.

For Black fans, yacht rock has always been part of the record collection. That’s another interesting narrative wrinkle that pushes against how this music is sometimes talked about.

Among the Steely Dan songs in the film, you have some of the expected ones—“Reelin’ in the Years,” “Bad Sneakers,” “Black Friday,” and “Peg”—but I think die-hards will be pleasantly surprised to hear “The Caves of Altamira.”

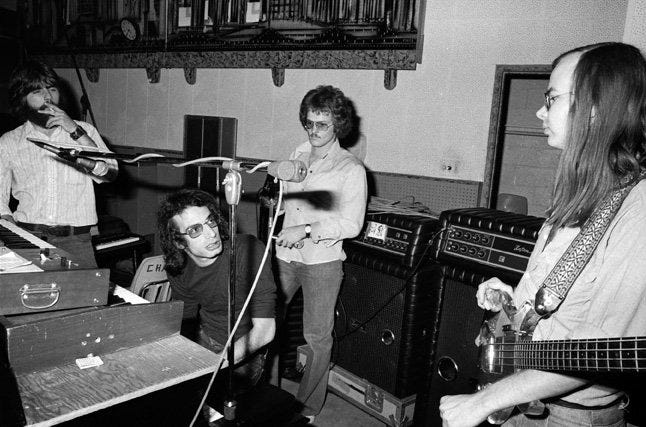

A deeper cut off The Royal Scam, definitely! And we needed “Bad Sneakers” and “Peg” because Michael McDonald sings on them. From a filmmaking point of view, Steely Dan is difficult because there’s not a lot of live footage of them from the ’70s. So we relied a lot on still photos, including some rarely seen shots.

Something I’d never seen before was a short clip of Fagen in the studio when one of the interviewees is talking about how Fagen had writer’s block after The Nightfly. Do you know where that footage came from?

We had an archivist who was digging through a lot of footage. It was challenging because Steely Dan stopped performing live in like ’74, and they did only a handful of TV appearances. The trick was editing the still photos in a way that made you forget you were just looking at photos of them. For all these yacht rock guys, really, there wasn’t a ton of footage, and some of it wasn’t in great shape.

At one point, the film was 20 minutes longer than it is now. Along the way you have to cut stuff out or put stuff in. And just for me personally, I was probably more of the “let’s put stuff in” person. But after seeing it with an audience, I’m glad it’s the length that it is. All the L.A. session stuff I really find fascinating. That could almost be another movie. Like the Porcaro brothers are a very interesting story on their own.

The film from the get-go has a feeling of forward momentum that makes it extremely watchable.

So many documentaries now are really long, or they’re multi-part movies. If it’s the right subject, that’s fine. But there’s also something to be said about a really tight movie that works.

Another thing I’m proud of with the movie is that there’s quite a bit of music focus. It actually goes pretty deep into why the music worked and how people approached it. It is less about the private lives of the artists and more about their creative lives, and I was really pleased about that. That’s kind of rare for a movie like this that is a general-interest movie on HBO. So many documentaries don’t actually talk about the art, how records are made, why the music is significant, or why it’s good. And I actually think that this movie does that in a pretty deep way for a 96-minute film. I know that the Expanding Dan reader out there is going to maybe want more from the Katy Lied sessions and “Why didn’t you talk about Gaucho?” And, look, I’m one of those people! I read your newsletter. But I think for what the movie is, there is a lot that will appeal to the superfans, and that is a hard needle to thread.

It’s a real feat that the film doesn’t pander to people who are already fans of yacht rock while also not getting so in the weeds that it alienates the general viewer.

With a movie like this, it would’ve been very easy to fall into certain motifs that are lazy but very attractive when you’re making a movie, like having jokes about boats or having comedians make fun of guys in mustaches. One thing I wanted to avoid, which you’ve seen in a lot of movies like this, is having the politics professor pontificate about how people were into yacht rock as a form of post-Watergate escapism. And it’s like, when has pop music ever not been about escapism? To me, that is always such a bullshit comment. Sometimes that sociological angle is relevant, but that was one thing I was like, “I don’t really want to do that.” We have some transitional montages for various years—like, in 1977, Elvis died, Three’s Company premiered, and Reggie Jackson hit three home runs in a World Series game. But that’s more about scene-setting and showing cultural change. It’s just a way to ground the viewer in a place in time.

It was such a relief to not have some professor onscreen saying, “Music became more commodified as Reaganism took hold.”

Yeah, like, “People wanted to hear ‘Sailing’ because it was Morning in America”—blah, blah, blah. That was something I made a point of saying, “I don’t think we need to do that. There’s enough here with the music and the stories of these musicians.” However, there is a narrative in the movie about how culture changed and how technology changed, especially the rise of MTV, and how that affected the popularity of these artists. At one point, we did have a beat about drum machines and the mechanization of making records and how suddenly you could just create things electronically. That’s implied in the movie now more than it’s shown. I think that comes across, even though we don’t say it as directly, but that was important. There is a sociological point we hit on in the film about the sensitivity of yacht rock artists, but again, it’s more grounded in the actual music than making sort of a broad cultural reach. We also talk about the motif of the fool in yacht rock.

I was pleased the film delved into “the Doobie bounce,” and how Michael McDonald’s piano figure from “What a Fool Believes” became a much-imitated musical motif.

It’s the best kind of observation, I think, because everyone’s noticed it but no one’s said it out loud. It’s an observation that resonates with an average listener because it’s very audibly obvious. Anyone can recognize it. I must shout out our editor, Avner Shiloah; I really love what he did with that sequence. And Garret, too, also was really deep into the editing of the movie.

I’ve also got to shout out Maddie Cross, who’s one of the producers of the film. She’s Christopher Cross’s daughter. It’s fair to say the movie would not exist without her. She was the one who really was integral in terms of getting all the musicians on board. And at the same time, she really understood what this movie needed to be, which was an affectionate movie, but not overly stage-managed by the artists. None of the subjects had editorial control over it. It’s not like we were out to make a hatchet job or anything, but I mean, there are critics in the movie. They’re mostly complimentary but not always. I think it is a pretty fair movie. Christopher Cross comes across great, but the film is frank about his struggles in the ’80s dealing with fame. And that’s Maddie’s dad. Her willingness to make a real movie while at the same time being able to get everyone on board was huge. She got her dad on board and Michael McDonald, and then once we got those guys, it was easier to get other people. That’s always the biggest challenge with these movies—getting the people on board and then getting the music. And a lot of times you have to cede a lot of editorial control to the subject in order to get interview access and music licensing. Thankfully, we didn’t have to do that.

Too many documentaries these days feel self-produced by their subjects.

Right, right. And that didn’t happen. And Maddie has a lot to do with that. Again, this wasn’t like an exposé or anything. It’s a very affectionate movie, and I think they all come across very well. But I know there are things in the movie that maybe wouldn’t be in other documentaries, mainly from the journalists and critics who are talking about the music.

While I was watching the film, I was thinking about the Beach Boys, because famously only one of them actually knew how to surf, and similarly, most yacht rock guys knew fuck all about seafaring. There’s a great line in the doc from Steve Lukather, who says, “I played on all those records. Where the fuck is my yacht?” These guys just happened to be in California, near a dock. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen photographic evidence of Becker and Fagen on a boat.

J.D. says at the beginning of the movie that yacht rock is not literally about boats. It’s music that sounds like a million bucks. It’s top-of-the-line music. That’s what they originally meant by the term. When I first heard the term yacht rock, I always thought it applied because a yacht is a smooth ride. I thought it was referring to the smoothness of the music. Among the musicians, that connotation of wealth has always been a bone of contention. But the term has been a positive, on balance, for everyone. I think it’s even been good for Steely Dan, because it opened the door for a lot more people to give them a chance and then go deeper into the catalog. And once you’re in, it’s like, “Oh, wow, OK. This is a whole other story.”

Enjoyed your discussion with Mr. Hyden! Looking forward to the documentary.

Minor editorial note: "cede," not "seed."

Ugh! I am—and not as a knee-jerk response, nor because Donald Fagen needs the likes of no-one-from-nowhere me (he doesn’t!) to champion him—easily in the camp alongside Mr. Fagen's “Go fuck yourself” to the filmmaker who, among others, places Steely Dan in the warm-fuzzy of anodyne sub-genre “Yacht”-rock, … and notwithstanding the filmmaker’s self-congratulatory (and self-aggrandizing?) posture that Fagen is somehow being ironic and not sincerely telling him to fuck-the-fuck-off.

[Aside: Even if Fagen is being ALSO humorous-ironic-sarcastic, his epithet is at least—as tropes such as Cliché and Passive-Aggressive also INCLUDE—a substantive truth: i.e., DON’T call “Yacht”-rock what Walter and I had been doing for a half-century now, namely investing in genuinely STILL nonpareil creative songwriting (that is, within music/lyrics; other genres/artists—e.g., novelists such as James Joyce, Thomas Pynchon, et al.—certainly can lay claim as avatars if not progenitors of the Becker-Fagen encyclopedic wit).]

I appreciate that YOU meanwhile call to attention the distinction between the sound- and sound-adjacency of indeed progenitors Becker/Fagen, then copied or mimicked or whatever by other bands … and Yes, too, by other musicians in the Dan pantheon. But none of that justifies Hyden’s presumption. I mean, just a for a quick-and-easy example: I love the Grateful Dead AND Joni Mitchell; and lo-and-behold, Garcia, et al., backed Joni here and there and on the “Court and Spark” album. But that does NOT mean that Joni’s music/lyrics have anything to do with Grateful Dead music/lyrics. Yeeesh!

Perhaps I’m in some minority or minor-plurality here, curmudgeonly or otherwise, and I don’t need to invoke some sort of argumentum ad populum, but as we don’t know each other, I will confess that fellow “deep” Steely Dan fans (some east coast; some west coast—all professionals/academics/touring-musicians, et al.—I’m an ol’ west-coast English Lit. guy and writer/poet/editor) indeed feel likewise: that Steely Dan’s music and especially lyrics are still ahead of their time, and in any case not relegated to one or another easy classification, and in EVERY case, certainly not in the same solar system … or galaxy … or universe as, say, the Yacht Rock of “Reminiscing” (Little River Band)—though, as Seinfeld would say, “…not that there’s anything wrong with [Yacht Rock]. :-)