A brief history of the session musician

In an excerpt from "Drums & Demons," his definitive new biography of Jim Gordon, Joel Selvin frames the legendary "Pretzel Logic" drummer in the grand constellation of studio players.

A few years ago, I wrote a letter to Jim Gordon in prison. I was in the thick of conducting interviews for my oral history of recording with Steely Dan, and I wanted to ask the legendary drummer about playing on Pretzel Logic, the 1974 album that saw Walter Becker and Donald Fagen leaning heavily on session musicians for the first time.

“While working as staff writers at ABC/Dunhill in Los Angeles,” Fagen had told me, “Walter and I got to see the players who were in the studios every day, including Jim Gordon, Victor Feldman, ‘Clean’ Dean Parks, and Larry Carlton. While we were thrilled to be working with the original Steely Dan group, we couldn’t ignore guys with that level of skill. Plus, some of our stuff required that kind of technique and experience.”

Daddy don’t live in that New York City no more.

But doesn’t Daddy still deserve a swell Father’s Day?

By the time Gordon showed up to the Village Recorders in West Los Angeles for the Pretzel Logic sessions in late 1973, he had firmly established himself as the most respected drummer of his generation, the heir to the great Wrecking Crew stickman Hal Blaine. He had backed everyone from the Everly Brothers to Frank Zappa. He had played on the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows” and “Good Vibrations,” George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain,” Harry Nilsson’s Nilsson Schmilsson. On Derek and the Dominos’ Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, he was credited alongside Eric Clapton as co-writer of the album’s eternal title track (though he would later be accused of pinching the melody of the memorable piano coda from a song he had written with his then-girlfriend, Rita Coolidge).1

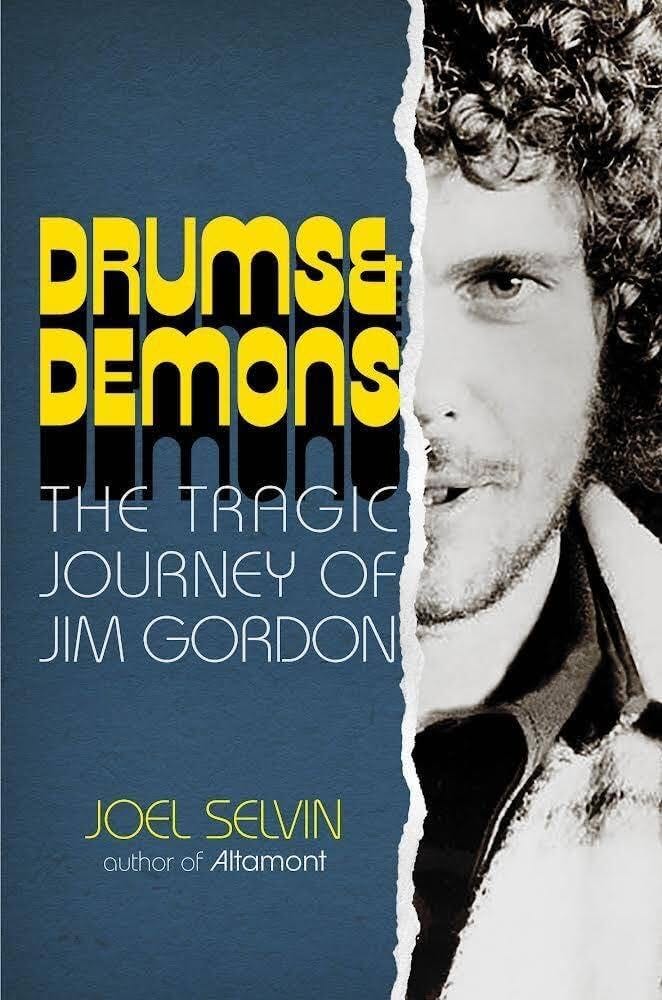

“No drummer had a greater career than Jim Gordon,” the veteran music journalist Joel Selvin writes in his latest book, Drums & Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon, published earlier this year.

What I was hoping Gordon could provide was his recollection of the atmosphere in the studio during the recording of Pretzel Logic, as he and Chuck Rainey and other first-call players began cutting tracks, including “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” “Any Major Dude Will Tell You,” and “Here at the Western World.” Did he sense any tension emanating from Jim Hodder, Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, and Denny Dias—the Steely Dan band members who looked on as their recording roles were significantly diminished or altogether eliminated?

I finished the note and sent it off to the California Medical Facility in Vacaville, located halfway between San Francisco and Sacramento. At that point, Gordon had been behind bars for nearly 40 years, serving a sentence of 16 years to life as a convicted murderer. Before his incarceration, he had been tormented for years by auditory hallucinations. The chorus of voices in his head progressively grew louder and more commanding. “Chief among his tormentors,” Selvin writes in Drums & Demons, “was his mother’s voice—harsh, critical, dismissive, and discouraging.”

It was the voice of his mother, Osa, that Gordon later said he was obeying on the night of June 3, 1983, when he arrived at the 71-year-old woman’s North Hollywood apartment with a claw hammer and a kitchen knife in tow. Upon entering, Gordon told his mother, plainly, “I’m going to kill you.” He struck her on the head with the hammer four times, then plunged the knife into her chest three times.

At trial, Gordon’s defense argued that the killing was the result of the 38-year-old musician’s undiagnosed schizophrenia. He was convicted of second-degree murder and would spend the rest of his life in confinement. On March 13, 2023, Gordon died at the prison medical facility in Vacaville. He was 77.

I can’t be sure my letter ever found its way to Gordon. It would have arrived amid the depths of the pandemic, when life in America’s prisons was even more brutal and chaotic than usual, as the virus spread with terrifying speed through crowded, vulnerable populations unable to properly distance or quarantine. Gordon’s concerns at that time would have been far more grave than satisfying the whims of a journalist’s curiosity.

And so, I never followed up.

“Jim was pretty impressed by the intensity of Steely Dan, even if he didn’t necessarily understand their methodology,” Selvin recently told me. The author relied on Dean Parks as his chief informant on the Pretzel Logic sessions, which earn a few paragraphs in the book. “Like, why this take and not that one? Oh well, who cares? I think there was a lot of that with Jim.”

It was Gordon superfan Jeff Porcaro, Selvin writes, who encouraged Becker and Fagen to hire the esteemed drummer. Gordon and Porcaro, separated in age by nearly nine years, had both attended L.A.’s Ulysses S. Grant High School. When they eventually teamed up on Steely Dan’s “Parker’s Band,” it was the thrill of Porcaro’s young life.

“Gordon was my idol. Playing with him was like going to school,” Porcaro said to Modern Drummer shortly before his death at age 38 in 1992.2 “His playing was the textbook for me. No one ever had finer-sounding cymbals or drums, or played his kit so beautifully and balanced. And nobody had that particular groove.”

Jeff Porcaro on Jim Gordon

In the midst of his chronicle of Gordon’s rise as a sought-after drummer and eventual descent into matricidal madness, Selvin devotes a chapter of Drums & Demons to the fascinating history of the session musician, framing Gordon in the grand constellation of studio players from King Curtis to Hal Blaine. That chapter is excerpted here with the author’s permission.