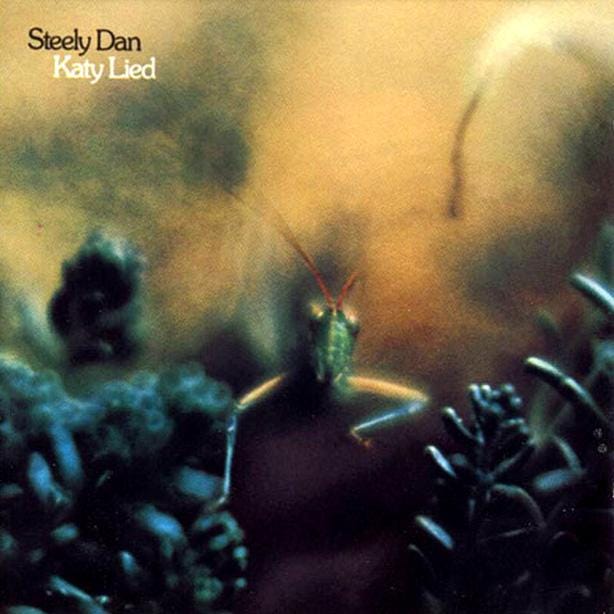

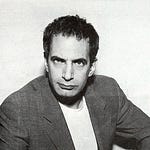

In February, Barney Hurley reached out with some good news. The English musician and I had been in regular contact for a few years, brought together by our shared preoccupation with Steely Dan. We would trade rarities and tracks that cribbed from the songbook of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, and he would send updates on the latest happenings with his jazz-rock project, Powder Blue Tux. This time Hurley was giddy to report that he was putting the finishing touches on a song that featured some major dudes from the Steely Dan session pool: guitarist Jay Graydon, saxophonist Tom Scott, trumpeter Randy Brecker, as well as the band’s longtime drummer, Keith Carlock. “I’ll send you a WAV,” he wrote, “as soon as it’s mixed and mastered!”

Last week came the shocking news that Hurley had died of cancer at the age of 54. Gavin Dodds, Hurley’s bandmate in the mid-’90s outfit Samuel Purdey, wrote in a Facebook post on May 18 that he had been informed “a month or so ago” that Hurley was in the hospital, “gravely ill” from Stage 4 cancer. During the explosion of grunge and Britpop, Hurley and Dodds swam against the tide, reviving the smooth, conspicuously unhip sounds of the ’70s a full decade before the reappraisal of “yacht rock.”

Making music was a labor of love for Hurley. He was gradually self-funding the Powder Blue Tux recordings by doing session work on TV and radio jingles and writing library music. The 2016 single “Container Zero” featured Graydon on guitar, Weather Report’s Peter Erskine on drums, and veteran Steely Dan band member Michael Leonhart on horns; it was mixed by Elliot Scheiner, the engineer who had mixed Steely Dan’s Aja and Gaucho, and Fagen’s The Nightfly; and it was mastered by Scott Hull, who had worked on Fagen’s Kamakiriad and Steely Dan’s Two Against Nature. The B-side, “Mayfair,” showcased Steely Dan ringer Elliott Randall on guitar.

“If I’m going to put my name to something,” Hurley once told me, “it has to be of a certain standard.”

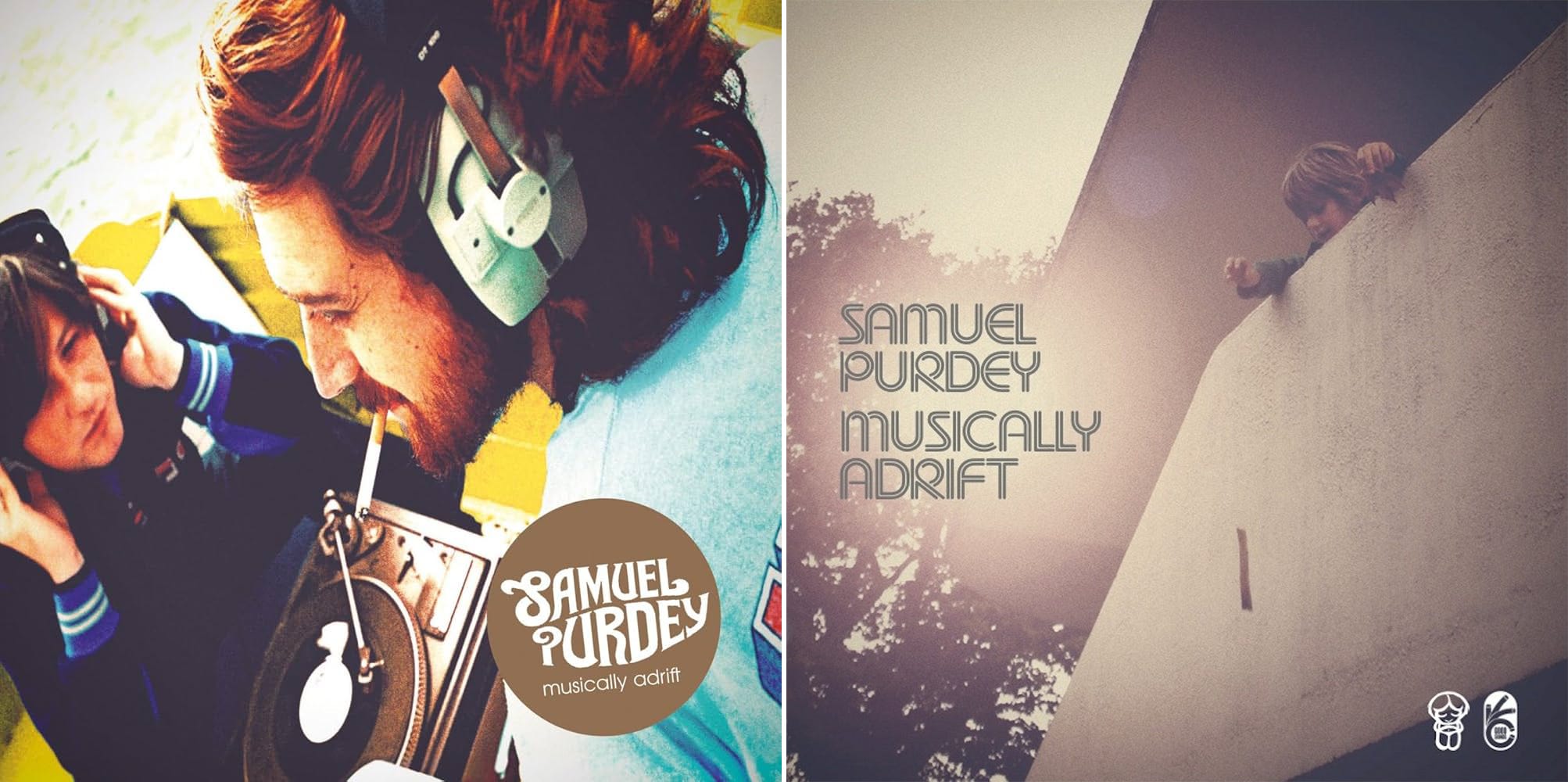

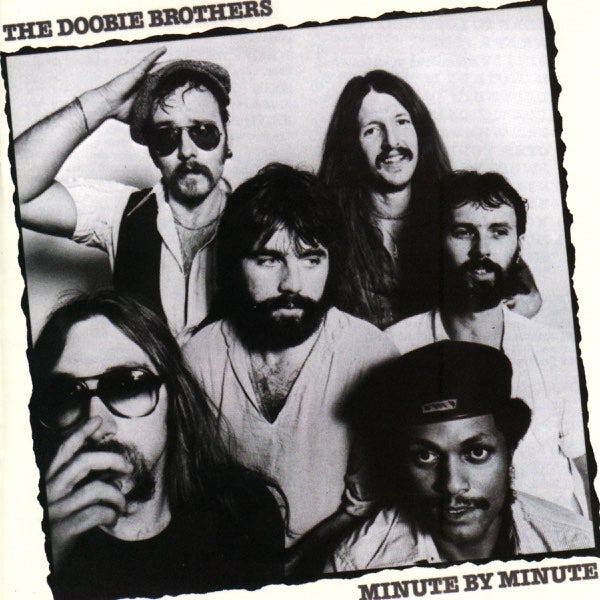

Before he got sick, Hurley had been looking forward to traveling from his home in Brighton to the States to work once again with Scheiner, who had mixed more than half of the tracks on the one and only Samuel Purdey LP, Musically Adrift. Hurley and Dodds recorded it in 1995, but Sony unceremoniously dropped the band when their singles weren’t hits, and the album was shelved. Musically Adrift finally saw release in 1999 on a Japanese label. Tummy Touch Records reissued the record widely in 2013, exposing it to an audience that by then had rediscovered Steely Dan, the Doobie Brothers, and Boz Scaggs, and saw Samuel Purdey as a kind of sunken yacht treasure.

During the pandemic, Hurley began regularly sharing on Twitter items from his massive collection of 1970s and ’80s music memorabilia. He posted little-seen photos of Steely Dan and related artists that he had acquired from estate auctions, in addition to autographed album covers, imported magazines, rare posters, obscure advertisements, and other ephemera.

“I am a Steely Dan fanatic, so I know that my fellow Danfans will get very excited when I post a picture that they haven’t seen before,” Hurley said. “New things still turn up. I just bought a few negatives from eBay that I’d never seen before, and there is quite a lot of stuff from magazines that are now defunct that I’ve yet to Photoshop. So there is more to come.”

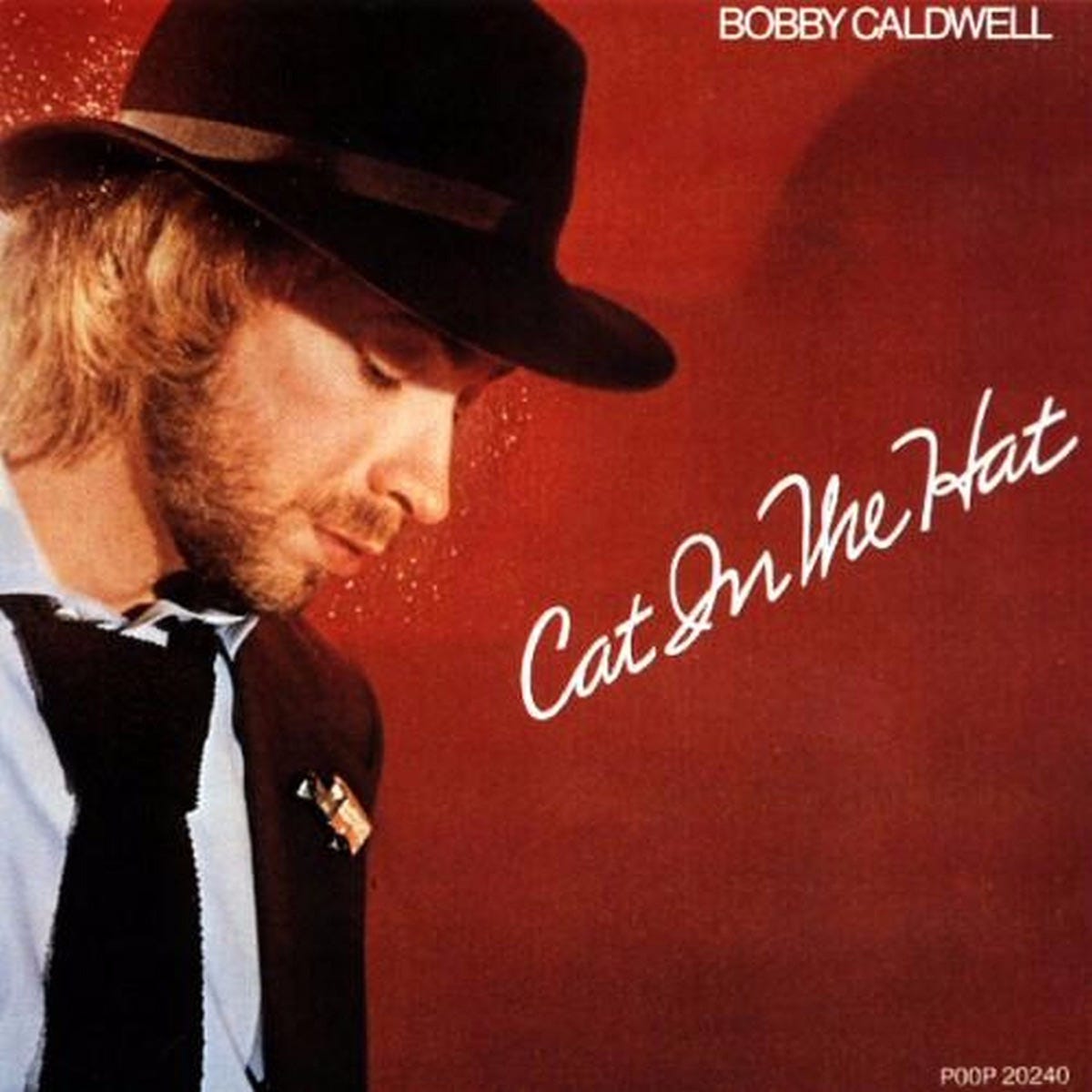

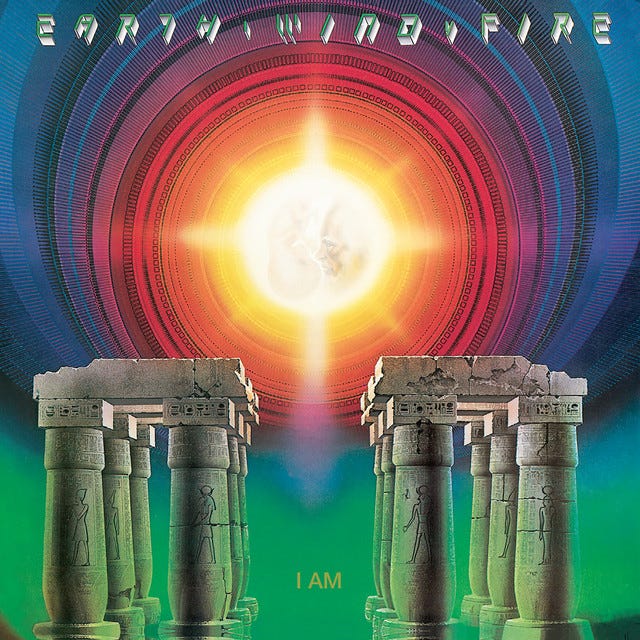

Back in 2022, Hurley sat for a lengthy interview that I had planned to publish upon the release of the Powder Blue Tux record. In the wake of his passing, I feel compelled to share that conversation now, in an attempt to pay tribute to him in some small way. We discussed everything from the origins of his abiding Steely Dan fandom to the challenges of making Musically Adrift—and he curated the above mixtape of songs that he said directly influenced Samuel Purdey. Transcribing our interview over the past week felt a little like hanging out with a friend one last time.

Where did you grow up?

I was raised in Brighton, where I am now, on the south coast. It’s only 45 minutes to Central London. They call it “London-by-the-Sea.”

When did you first get into stuff like Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers?

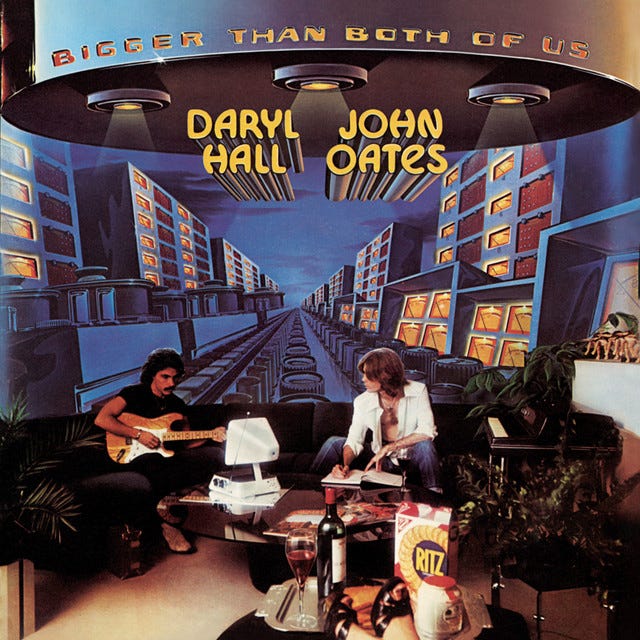

My mom and dad are both teachers who happened to have great taste in music. Lots of people’s parents had very boring record collections. I’d go to friends’ houses when I was five or six, and think, They hardly have any albums! I’d look through, and there would always be Carole King’s Tapestry, but there wouldn’t be any Joni Mitchell or Steely Dan or Earth, Wind & Fire or George Benson. I was just lucky that Steely Dan, Hall and Oates, Weather Report, Stanley Clarke—all those artists were just there in my house growing up. American bands would play at English universities a lot, so my parents went and saw Rufus & Chaka and Zappa and stuff while in college. So I owe it all to my parents, really. Listening to drummers is how I learned to play. I started when I was four, hitting knitting needles on the wicker basket where my mum kept her wool. My dad thought, Oh, he’s quite good.

As I got into my teens, I became a really bad vinyl junkie and still am. I lived in New York from ’90 to ’93, and that was exactly when people were ditching their records and replacing them with CDs. So all the thrift stores were just slammed with vinyl, and I’d ship them back to England. I’ve got three-quarters of them in storage, because my son took my music room, as they do. I’ve got about a thousand records in the house.

I’ve got to imagine that when you were a teenager in the mid-to-late ’80s, most of your friends were not listening to jazz-rock and R&B from the ’70s.

No, they were not. For Generation X, Steely Dan was the music our parents listened to, so it was really fucking uncool. I’ve always seen Steely Dan as a genre within itself. It’s a bottomless pit of joy. I’ve never understood a musician who says, “I don’t like Steely Dan.” I think it’s because you can’t fucking figure out that guitar solo! If you’re a pianist, a drummer, a bass player—every performance is unreal.

During my teens, around 1988, there was a thing where artists were name-checking Steely Dan. I remember Kate Bush being quoted in a magazine saying how much she loved Steely Dan. It was notable to me because up till then, everyone was saying they sucked.

Gary Clark from Danny Wilson has said that he found his voice by listening to Steely Dan and Fagen’s The Nightfly.

I loved the Danny Wilson song “Mary’s Prayer.” There’s a little piano tag on the end of one of Danny Wilson’s songs that is a Michael Omartian tag. Just like at the end of the Powder Blue Tux song “Container Zero,” I do the piano tag from the end of “Throw Back the Little Ones,” just to say, “Yep, you guessed it—I’m a Danfan.” There was also a band called the Kane Gang. And Paddy McAloon of Prefab Sprout is incredibly gifted.

It took guts for you to stick by what we now know as yacht rock at a time when that was considered totally passé.

In the mid-’90s, there was this huge Britpop push—Oasis, Blur, Pulp, all these bands. I remember people saying to me, “Do you like Oasis?” “No.” “Do you like Blur?” “No.” They were sort of like, “What’s with you?” People were mentioning Oasis in the same sentence as the Beatles, and to me that was just insane. I can’t really play guitar, but I promise you I can play every Oasis riff. I remember Phil Collins saying, “It took me a while, but I really got into them.” I never got into them. Blur did a couple of things that I thought were OK. And Pulp, I like the lead singer, and they’re humorous. And then there was Jamiroquai and the Brand New Heavies, which was labeled acid jazz—which essentially means jazz-funk.

When I was 17, I moved to London and got an apprenticeship in a recording studio. I didn’t want to be a recording engineer, but I knew I wanted to be around music and musicians. Basically I was just making coffee, but I watched the engineers and figured out things like what a patch bay is. Robbie Gordon, Gil Scott-Heron’s bass player from the mid-’70s to the early ’80s, was recording an album there. The drummer had flown back to Chicago, and the label wanted to release a specific track [“Dat’s Slammin'”] as a promo single. Gordon said, “The drumming, it’s not funky enough.” I said, “Oh, I can do it.” He was really nice: “I didn’t realize you could drum. The kit is set up. Go and do it.” I didn’t have to make coffee anymore after that.

Through that, I did a tour with Jamiroquai. Gavin Dodds, the cofounder of Samuel Purdey, was the rhythm guitarist with Jamiroquai on that tour.

Is that where you and Gavin first met?

No, we knew each other. He was a friend of my brother. It was just one of those weird things, like, “Gavin, what are you fuckin’ doing at this rehearsal?” The bass player was Stuart Zender, who played on the Samuel Purdey album, and he’s incredible. After playing those [Jamiroquai] songs so many times, we were so fucking bored with that jazz-funk shit. We were listening to [Joni Mitchell’s] The Hissing of Summer Lawns and Tower of Power and James Taylor, and Gavin and I realized that we had similar taste in music. Because we had just gotten off a tour with a Sony artist, that made us interesting to record executives. We also had a very good manager who essentially said to us, “I’ll get you a deal.” There was money in the industry then, and they assumed we were going to be the next Brand New Heavies or Jamiroquai. There was a lot of jazz-funk elements in what we were doing, without a doubt, but they didn’t expect the soft-rock element.

The name Samuel Purdey—where did that come from?

Purdey is a British gunmaker. We were thinking of it in relation to Steely Dan, because it also sounds like a guy’s name.

What was your vision for the record?

I just wanted to make an album that I liked. I call Gavin “Donald McDonald,” because his voice naturally sounds like half Donald Fagen and half Michael McDonald. But, to be honest, I never actually thought that the Samuel Purdey album sounded like Steely Dan. Sometimes we would find ourselves with something that sounded a little bit like a Boz Scaggs song, and I’d say to Gavin, “Do you realize how many copies of Silk Degrees were sold? People are going to notice the similarity.”

I remember Gavin and I had a meeting with some Sony executives. I wanted Arif Mardin, Tommy LiPuma, or Billy Joel’s producer [Phil Ramone] to produce the Samuel Purdey album. They said, “No, that’s a million-pound album. We are giving you 300 grand.” So they stuck us with two of their hand-picked producers. One lasted about half an hour, the other one lasted a day. One day, Gavin and I were working with a Fender Rhodes, putting it through a phaser pedal and all these things, and this producer came in and said, “What are you doing?” We said, “We’re figuring out what we want the Fender Rhodes to sound like.” We wanted everything to sound great. He was like, “It’s a Fender Rhodes. Just plug it in.” I thought, This is not going to work. That was the guy who lasted about five minutes. The guy who lasted a day was very nice, but you could just tell he wasn’t going to be good. Even though he had produced some hits, it was nothing that I particularly liked.

It ended up being me at the console with the engineer. We went through about five engineers until we found one who was really good—Brian Tench, who had produced two Bee Gees albums with Arif Mardin and engineered Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love. Brian came in and said, “I really like the songs and think you’re really good, so I’m going to come down in price.” He cost about £1,000 per day as an engineer, but he came down to around £600 a day.

My lack of experience at producing meant that it took a long time, because producing a record is one hell of a job. There are so many issues that can turn up on track that you don’t expect, things that make you go, “What’s that fucking sound?” And then the studio maintenance guy would come in and be like, “I think it’s bias bubble.” Like, “What is bias bubble?”

When did you finish the album?

We recorded it in ’95. In January 1996, I went to Westport, Connecticut, for five or six weeks to mix with Elliot Scheiner. He had mixed Gaucho and The Nightfly! One of the happiest moments of my life was when we were sitting at the console, and I was like, “Elliot, can you take that fader down a bit?” And he was like, “Hey, Barney, you know you’re really fucking nitpicking.” I was thinking, Oh! The guy who mixed The Nightfly said I’m nitpicking!

When you were mixing with Elliot, did you hit him up for Steely Dan stories?

Every time we took a break for lunch. When you’re stuck in a room with someone for a month or so, you get loads of stories. I asked him what he thought about Kamakiriad, and he was like, “I didn’t think it sounded that great.” But I love Kamakiriad. Elliot tended to be really into things that he was involved in, and stuff he wasn’t involved in, he was kind of like, “Meh.”

I was really happy with all of the mixes because it’s fucking Elliot Scheiner. But when we got back to Sony, the execs said, “It’s too perfect.” Six of Elliot’s mixes were cool with them. They wanted the others remixed. It really tore me apart. I said no, and our manager was like, “You can’t really say that.” So luckily they suggested Bob Power, who had just won a Grammy for Erykah Badu, and he had mixed A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory. His mixes weren’t as bright and shiny as Elliot’s mixes. Elliot would do things his way, and if you’d say, “Can you put up the bass?” he’d say, “I’ll put it up half of a db.” I’d be like, “Gee, thanks.” But Bob on the other hand would say, “Look, man, this is your record. I may never hear it again. So you’ve got to be happy with it.” Bob remixed the first single, “Lucky Radio,” and then they stuck us with a British guy to remix the other three songs. Do you remember that track “Return of the Mack”?

Of course.

He had worked on that, and it was a big hit. So he was seen as Mr. English Slick R&B Guy. And I thought, But I fucking hate that song. Just watching him in comparison to Bob Power and Elliot Scheiner, it was just like, “Fucking hell!” But there was nothing we could do about it.

Which tracks are the Elliot Scheiner mixes?

“Whatever I Do,” “Valerie,” “Soon Comes Another”—he did six out of the 10. Seven of 11, if you count “Help Me See,” the bonus track for the Japanese release.

Then came more misfortune. The guy who had signed us had a lot of success in the ’80s, but not much success in the ’90s. He was a big Danfan, a big Doobies fan, and he got us. He’d come into the studio and say, “Oh, I love the harmonies on that!” But then he got fired. Someone came into the department to get rid of anyone who wasn’t signing bands that were having hits. You need someone at the record company on your side to fight your battles, and when he was gone, we were left with this guy who clearly didn’t give a shit about us. We had just done a gig at the Jazz Cafe in London, and the next day we were going on a world tour supporting the Brand New Heavies. So we were all ready for that, and the guys in Brand New Heavies were really looking forward to it. And then that morning, our manager got called in for a meeting, and it was just like, “It’s over. We’ve spent 300 grand, two singles are out, and they didn’t hit. Sorry.” Simple as that.

They told you they would not be releasing the album?

Yeah. People were getting fired and bands were getting dropped, and we happened to be one of them. They gave us the master tapes and were like, “See ya.” After we got dropped from the label, the Samuel Purdey album was dormant for a few years until it got put out in Japan in 1999. Still, we didn’t have a title.

How did you land on Musically Adrift as a title?

It was a line from The New Musical Express, which had done a hit piece on us after our first single. The story was headlined “Samuel Purdey Find Themselves Musically Adrift.” Our manager said, “Usually they don’t do this on the first single, so I think they really fucking hate you.” I realized then how horrible a journalist could be. It was a long interview, and I was saying how much I loved Nirvana and was talking about different types of music and what we were listening to at that time. I’d said I was listening to Boston’s “More than a Feeling” that morning. It was a nice, friendly interview, but then the guy just destroyed us. He took things I said completely out of context.

When Musically Adrift was reissued worldwide in 2013, it got great reviews. Ironically, the NME guy who wrote the hit piece, Paul Moody, gave us the best review, writing in Q Magazine that at its best the album “achieves rock’s Rosetta Stone: timelessness.” He had completely forgotten about his hit piece! It just showed how disingenuous the whole thing was. Gavin rung me up and said, “I dunno whether to laugh or cry.” I just laughed. Because yacht rock is now seen as hip, it’s no longer illegal to listen to Samuel Purdey. But it was nice to read the reviews. It felt kind of like validation.

But what it ultimately comes down to is what Quincy Jones once said to David Foster, when Foster asked what his secret was: “David, three things: the song, the song, and the song.”

And Samuel Purdey had great songs.

Well, we tried our best. I can only hear the flaws now. I can’t listen to it. We’ve just done a 10-year deal with Tummy Touch Records, the label that put it out on a more worldwide scale. I want to master with Scott Hull at Masterdisk in New York, and I’m not looking forward to it, because I know I will have to listen to the album again. After you’ve written the song, recorded it, mixed it, and mastered it, you never want to hear the fucking thing again. [Laughs.]

So you can relate to Becker and Fagen’s angst over the years whenever they had to revisit their early albums like Can’t Buy a Thrill?

I can understand that, because it was their first go, even though I can’t hear a single flaw in that album. When they got the Rolling Stone cover in ’74, the teaser line was “Steely Dan comes up swinging.” It is so true. For guys in their 20s, their music was just so sophisticated and lyrically oblique. There are bands, like Little Feat, that come out with a really good first album—but not as good as you Can’t Buy a Thrill.

I heard that during the remastering for the Citizen Steely Dan box set, every 10 minutes, Fagen would be like, “I can’t handle it,” and just get up and leave the room. He couldn’t bear listening, especially to the early stuff. Walter Becker and Roger Nichols were laughing, like, “Oh, Donald, come back in.” But he just couldn’t handle it. He hated hearing his own voice.

My favorite singers don’t have traditionally “good” voices.

And I love Fagen’s voice. He’s not Ray Charles. But that’s what makes it so great for me. His voice was a staple of the ’70s.

Why didn’t Samuel Purdey do a second album? Was it because you and Gavin didn’t want to risk going through another traumatic experience?

In Japan, Musically Adrift did really well, and “Lucky Radio” was number five on the Tokyo Hot 100, between Ricky Martin’s “Livin’ La Vida Loca” and TLC’s “No Scrubs.” We were hoping a Japanese label would give us a budget to record, but they didn’t go for it. Even the Powder Blue Tux single cost thousands. Bob Power mixed a track, and he’s not cheap. Elliot Scheiner mixed a track, and he’s not cheap. Michael Leonhart, who did the horn arrangements, is not cheap. Jay Graydon is not cheap.

Jay is a lovely guy. He’s nocturnal. I asked his assistant, “What’s a good time to call Jay?” She said, “Now.” I said, “It’s 4 a.m. in Los Angeles!” She said, “No, no, he’s up.” I tried him, and he’s like, “Hey, Barn!” Fucking hell. He says he keeps those hours because he’s working and doesn’t want anyone to bother him. He just wants to work.

You once said to me, “Who would’ve known that this kind of music”—what’s now called yacht rock—“would be revered in the way that it is now.” Have you felt any measure of redemption over the past couple decades?

After Two Against Nature came out, I bumped into a guy who used to take the piss out of me—“You like Steely Dan?”—and he was like, “The new Steely Dan album is fucking amazing, isn’t it?” Steely Dan winning the Album of the Year Grammy must have made him think, Oh, there must be something about this band to have beaten out Eminem! Being English, it’s all about Lennon and McCartney. And I like the Beatles. Who doesn’t? If you don’t, that means you don’t like music, really. But for me, it’ll always be Becker and Fagen.

Share this post